Report Outline

I. Introduction

II. Mandate, observations, and background

III. Accountability and supervision

IV. Transitions and release from ministry

V. Concluding observations

VI. Recommendations

Addenda

A. Updates to Church Order Articles 12-13 and Their Supplements

B. Updates to Church Order Articles 8, 14-17, and 42 and Their Supplements

C. Covenant of Joint Supervision for Ministers of the Word and Commissioned Pastors Serving in Noncongregational Ministry Positions

D. Separation Agreement Template

E. Guidelines for Pastors and Congregations in Times of Conflict

F. Resources and Forms Related to the Calling, Supervision, and Release of Ministers

I. Introduction

Over the past several decades, the Christian Reformed Church in North America has seen an increase in the number of issues and concerns related to the calling and supervision of ministers of the Word in what are often called “specialized ministries,” and to the release of ministers from congregations and/or from the denomination as a whole. One of the more common concerns relates to Article 17 of the Church Order because actions related to this provision often bear a stigma for pastors and churches. This concern has caused a number of individuals and churches to suggest changes to our way of handling these kinds of situations as a denomination. Some of the concerns and suggested changes are highlighted in Overtures 4, 5, and 6 deferred from 2020 to be addressed by Synod 2022, and in Overture 10 to Synod 2022. These overtures suggest that our churches and classes would be helped by clearer guidelines and possible changes to Church Order provisions related to the supervision and release of ministers.

As a result of these discussions, Synod 2022 approved the establishment of a Church Order Review Task Force (CORTF) (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 849). Following the parameters of composition and membership delineated by synod, the task force was formed with the following members: Rev. Laura de Jong, Rev. Chelsey Harmon, Pastor James Jones, Mr. Casey Jen, Rev. Rita Klein-Geltink (reporter), Rev. John Sideco, Rev. Kathy Smith (ex-officio), and Rev. Joel Vande Werken (chair). The task force was also assisted by advisors Rev. Dave Den Haan (Thrive) and Rev. Susan LaClear (Candidacy Committee), and we gratefully acknowledge the administrative assistance provided by Cassie Beadle and the wisdom of other denominational staff with whom we consulted.

The mandate of the task force has been as follows:

to conduct a comprehensive review of Church Order Articles 8, 12, 13, 14, 16, and 17 and their Supplements in conversation with Pastor Church Resources [now called Thrive] and relevant voices, and to bring an interim report to Synod 2023 through the COD and a final report to Synod 2024.

The task force shall develop suggestions for clearer guidelines to pastors and churches in times of conflict, as well as assistance for positive pastoral transitions and more effective oversight of individuals in specialized ministries, including attention to the readmission of pastors via Article 8.

(Acts of Synod 2022, p. 849)

The task force met on a number of occasions via Zoom (Nov. 7 and Dec. 5, 2022; Feb. 28, Apr. 11, May 23, July 17, Aug. 22, Sept. 25, Oct. 30, Nov. 9, and Nov. 20, 2023) and conducted one in-person meeting in Grand Rapids, Michigan (Feb. 1-2, 2023). The task force submitted an interim report through the COD to Synod 2023 (Agenda for Synod 2023, pp. 72-73). And here, following regular updates to the Council of Delegates and interactions with a number of individuals across the CRCNA, the Church Order Review Task Force presents its full report to Synod 2024.

II. Mandate, observations, and background

A. Initial Observations

The Church Order addresses a wide variety of situations in Articles 12-17. While it is important for the church to have agreed-upon processes to regulate its organization,it is not possible to create a separate set of rules or procedures to address every situation. In fact, it is expressly not the purpose of the Christian Reformed Church Order to do so. Dating back to the time of John Calvin, the purposeful practice within the Reformed tradition has been to create guidelines grounded in theological commitments that enable the church to function in a healthy and peaceful way (1 Cor. 14:40) and which allow for both flexibility and wisdom to be used in any particular situation.

Because our polity is rooted in a deep commitment to the creeds and confessions, these statements of faith provide the conceptual guidance that allows us to have a relatively “thin” Church Order that does not need to anticipate or address every eventuality but provides general guidance, with the assumption that other denominational resources will be available for particular situations. As the introduction to the Church Order states, these articles contain the “collective wisdom of the church” so that this wisdom might be “passed on from generation to generation.” The task force committed to carrying out its mandate in the same spirit. Thus we recognize that the following guidelines may seem too general for some situations, but we believe this approach is necessary and appropriate within a covenant community seeking the wisdom of God’s Spirit for their particular situation. And while we believe that good structures and policies can contribute to healthy church life, we also humbly recognize the limits of Church Order to address concerns that may arise. On many occasions as we carried out our work, we were reminded of the importance of covenant community and relationship building, and we encourage pastors, councils, classes, and any others who are involved in the issues addressed in this report to recognize Church Order as no more than a tool—a good tool, but only a tool—that points us toward deeper and healthier relationships rooted in Christ.

One particular issue the task force was asked to recognize was “the increasing use of Article 17 and its often-perceived stigma” (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 849). Of all the areas covered in this report, the discussion concerning appropriate application of Article 17 arouses the strongest feelings, because the article is often applied in situations of conflict and pain for both pastors and churches. While synod’s mandate primarily addresses the need for administrative guidelines and potential updates to the Church Order, the task force is also keenly aware that behind every situation involving transition and supervision are real people and real ministry situations. Our goal is to help churches and pastors find ways to address these situations in community rather than in isolation, with a balance of grace and truth that reflects the ministry of Christ. We also acknowledge that the increased use of Article 17 is due in part to a rise in the release of ministers for nonconflict related reasons, such as the pursuit of further degree studies, family care leave, spousal job changes, and the disbanding or disaffiliation of congregations.

1. Organization of this report

As we began our work, we recognized two broad areas of discussion within our mandate. First, we faced several issues dealing with supervision, accountability, and support for ministers of the Word in noncongregational settings. These issues roughly corresponded (but were not limited to) matters addressed in Articles 12-13. Second, we identified a number of issues related to transitions in ministry, especially when a minister of the Word is released from a particular call without another call in place, or when a minister resigns from ordained ministry in the denomination as a whole. These issues roughly corresponded to (but were not limited to) matters addressed in Articles 14 and 17. This report will largely use these two areas as a framework for organizing the material we reviewed as we carried out synod’s assignment. For each of these two main sections, we will attempt to meet four objectives:

- provide background observations and theological reflections

- identify key issues, observations, and concerns arising in today’s context, with particular attention to those named in the overtures referred to the task force

- note resources and guidance available within the denomination

- provide recommendations for the improvement of the Church Order and its Supplements, as well as potential action steps by denominational assemblies or staff

We also intend, in this first main section of our report, to offer observations about the theology of office and ordination that guides our thinking as a denomination. While there are a number of practical and pastoral considerations to keep in mind as we process matters related to a specific call, or to a release from a specific ministry, it is essential for the work of the church that we keep in mind the overall goal of advancing the work of God’s kingdom. Thus we want to ground all of our work, including those matters that appear more administrative in nature, in the testimony of Scripture and in the wisdom of theological reflection done within the Reformed tradition over the years. We hope to return to some of these reflections in the concluding section of our report as well (see section V, B), before providing a summary of our final recommendations to synod.

2. The limits of our mandate

It is also helpful to recognize the limits of our mandate. First, we note that a number of issues that could be related to the calling and supervision of ministers of the Word are not covered in the articles of Church Order assigned in our mandate. To begin with, we were not tasked to reconsider the definition of the “ministry of the Word” (Art. 11). Thus we will assume the validity and usefulness of that definition. Nor does our mandate cover issues related to bivocationality and the support of bivocational ministers by their councils (Art. 15). Those topics have already been addressed by the Study of Bivocationality Task Force (see Agenda for Synod 2023, pp. 285-314; Acts of Synod 2023, pp. 962-67, 975), and we found that their report provided helpful observations and insights about the changing nature of ministry today. Our mandate also does not specifically call us to address the supervision of retired ministers (Art. 18), though we will make some observations about this task (see section V, A, 2). In addition, with Overture 4 (deferred from 2020): “Amend Church Order Articles 12, 13, 14, and 17 with Respect to Supervision and Transition of Ministers,” we observed that many of our discussions about ministers of the Word could foster similar dialogues about commissioned pastors, a subject to which we will return in our conclusion (see section V, A, 1). Because these matters are outside the scope of our mandate, we will explore only in limited detail the applications of our work in those areas.

3. Terminology

For the sake of simplicity, we will use the terms “pastor” and “minister” throughout this report as synonyms for “minister of the Word,” the technical term for the office under discussion in Articles 12-17. We recognize that these terms could also apply to some persons serving in the office of commissioned pastor, so we want to clarify at the beginning of this report that, unless otherwise noted, our observations about officebearers in the CRCNA are limited to the single office under consideration in Articles 12-17.

We also tried to determine the best way to describe pastors who are not serving in a local CRC setting. For many years the CRC described these positions as “extraordinary” (for example, see Acts of Synod 1971, pp. 55, 643). More recently, the language of “specialized” ministries has been used (see Church Order Supplement, Art. 13-b). Neither term, however, is satisfactory in our present context. “Extraordinary” implies there is something unusual or unique about a particular calling, but such a term hardly seems appropriate for a rapidly growing number of positions beyond the local congregation. Additionally, congregations are increasingly creating “specialized” ministry positions, bringing confusion when the term is only intended to apply to positions outside the local congregation. Thus we have chosen to identify these roles as “noncongregational,” with the understanding that this term also has limits because it may include calls to congregations outside the CRC. However, we believe the term is the best one available to describe positions outside a local CRC congregation, provided we bear in mind the term’s application to the on-loan or orderly-exchange provisions as well.

Finally, as Overture 4 observes, the language of Church Order has been somewhat inconsistent in the way it refers to the nature of calling and supervision, and churches and pastors could benefit from further clarity about the church polity expectations involved in these related concepts. Again, there are limits to any terminology we might choose, and some of the confusion about terminology reflects the growing influence of corporate structures on the organization of the church. However, we also recognize that there is no single theological term that applies to the specific avenues for ministerial service covered in Church Order Articles 12-17. Thus, while we will use a variety of terms in this report—including “role,” “work,” “task,” and “ministry”—we have opted to recommend changes to the Church Order that use the term “position” consistently to refer to the specific call in which a pastor is supervised.

B. Theological reflection on the nature of office

The present version of the Church Order has its basis in the revisions approved by synod in 1965, but the principles behind our Church Order date back much further. We begin with a theological consideration of the nature of office as a recognition that our Church Order and practice must flow from our theology, and not the other way around. The Belgic Confession (Art. 30) teaches that the work of a pastor is to “preach the Word of God and administer the sacraments.” Together with the elders and deacons, pastors “make up the council of the church” and provide for the faithful ministry of the church. The Belgic Confession draws on biblical principles emphasizing the need for leaders who “preach the Word” and who “correct, rebuke, and encourage” the development of sound doctrine and care for God’s people (2 Tim. 4:2-5; see also Acts 6:4; Matt. 18:18). Traditional forms used in the CRC for the ordination of ministers of the Word similarly emphasize the tasks of preaching, administering the sacraments, prayer, and shepherding the people of God in the Christian life (see Psalter Hymnal 1987, pp. 992-93, 995-96). These tasks receive a formal summary in Church Order Article 11, which declares: “The calling of a minister of the Word is to proclaim, explain, and apply Holy Scripture in order to gather in and equip the members so that the church of Jesus Christ may be built up.”

The CRC’s understanding of the nature of ecclesiastical office is based to a significant extent on two synodical study committee reports. Synod 1973 received a report titled “Ecclesiastical Office and Ordination,” which looked at the “nature of ecclesiastical office and the meaning of ordination as taught in Scripture and as exhibited in the history of the church of Christ” and considered “the question of the ministerial status of ministers engaged in extraordinary types of service—like Bible teaching in high schools or administrative duties” (Acts of Synod 1973, p. 635; see Acts of Synod 1971, pp. 55, 643). Synod acknowledged that while some individuals are appointed to special tasks, the offices are to be understood in terms of functionality and “are primarily characterized by service, rather than by status, dominance, or privilege. The authority . . . associated with the special ministries is an authority defined by love and service” (Acts of Synod 1973, p. 715).

Twenty-eight years later, Synod 2001 received the report of the Committee to Study Ordination and “Official Acts of Ministry” and adopted “guidelines for understanding the nature of, and relationships among, the concepts and practices of ordination, the ‘official acts of ministry,’ and church office” (Acts of Synod 2001, p. 503). Among several recommendations adopted by Synod 2001 from that report, these two regarding leadership continue to define our view of office and leadership today:

Leadership is centrally a relationship of trust and responsibility. Leaders are entrusted by Christ, the great shepherd of the sheep, to take pastoral responsibility for a part of his flock. With this responsibility comes the authority of Christ for the purposes to which the leader has been called. . . .

Leaders must at the same time be recognized and trusted by the people of God as those who come with authority and blessings from the Lord. This dual relationship of leader to Christ and leader to the people is what above all defines leadership in the church. Leaders are those who have both the call of Christ and the call of the people.

(Acts of Synod 2001, pp. 503-4)

These reports offer a helpful summary of the CRC’s understanding of the nature of ordained ministry, which guides the application of Church Order to particular situations. And the important emphases on service and leadership continue to shape our denomination’s approach to ordained ministry, especially to the work of a minister of the Word, to varying degrees in varying situations in the present context. This theological and pastoral summary leads to some additional reflections on specific theological issues to which we will return throughout this report.

1. The nature of a minister’s call

In the Reformed tradition the office of minister of the Word is shaped by both an internal call—that is, a personal sense of the Spirit’s nudging toward leadership in the church—and an external call, extended by the church through its assemblies. Thus a call to ministry, and to a specific ministry, is not simply a matter for personal discernment but one that also involves congregations, councils, and classes in the deliberative process. Ministry has historically been seen as a lifetime vocation that can be given up only in exceptional circumstances, as reflected in the language of Church Order that refers to pastors who “forsake the office” (Art. 14-c). Because ministers of the Word exercise their office on behalf of the wider church, it is also the office most specifically and extensively regulated by Church Order, both in terms of training and of accountability to the assemblies.

Because a minister’s call is one considered in conjunction with other church leaders, the church has a special role to play in discerning calls to noncongregational positions. However, the classis and synodical deputies play an additional role of discerning whether a position outside the local congregation provides an appropriate avenue for service in ministerial tasks with the endorsement of the church. Some positions are considered to be preapproved for ministers of the Word, such as missions, chaplaincy, specialized transitional ministry, and synodical appointments or appointments ratified by synod (Art. 12-b). Other positions must be approved by classis with the concurrence of the synodical deputies as work that is “consistent with the calling of a minister of the Word” (Art. 12-c). In all calls, whether to congregational or noncongregational positions, the classis plays a role through its designated counselor (Art. 9).

Collective discernment is also required as ministers transition out of a particular call. The relationship between church and pastor is different from the relationship between a typical employer and employee. The CRC holds that pastors are not simply hired but that God is acting through the call of the congregation to bring a pastor into a specific place of ministry. This understanding is reflected in the questions asked of a pastor at an ordination or installation service. Thus ministers may not leave an existing call without the consent of the council that issued the particular call (Art. 14-a). Further, CRC polity also prevents a congregation from dismissing a pastor simply because they no longer appreciate his or her ministry. The calling process and polity assume that both a community left behind and a community being entered should take part in the discernment process concerning a pastor’s ministry. In addition, the wider church participates in this discernment through the involvement of classis functionaries or, on specific occasions, synodical deputies.

2. Ordination clings to a role in the church

CRC theology and practice tie ordination to an office, not an individual. Not only are the church assemblies involved in discerning a general calling into ministry, but also each ordained pastor requires a valid call from a church council in order to maintain standing as a minister of the Word in the CRC. This means that both pastors and councils must take the calling process seriously enough to see it as more than just a decision to “hire” or “fire” a church employee, or to “accept a position” with a particular employer. A pastor is not a “free agent” who can decide on the basis of personal preference where and when to serve in ministry. Thus Church Order insists that only those “officially called and ordained” may exercise office (Art. 3-b) and requires the consent of a council even when a pastor leaves a particular congregation (Art. 14-a). These requirements reflect Scripture’s warning about persons who seek to represent the church on their own personal authority (see Rom. 16:17-18; 2 John 10-11).

Further, though the ministry of the Word has traditionally been seen as a lifetime vocation, the CRC has never considered lifetime ordination as an automatic privilege (although this principle comes to expression in different ways for a minister of the Word than for the other offices). Synod 1973, as it considered a significant study on the nature of ecclesiastical office and ordination, observed that ordination recognizes a minister’s calling to a particular task—namely, that of preaching the Word and administering the sacraments in a certain setting. Thus ordination confers not a special status on an individual but rather the fact of their being set apart for a particular ministry that is strategic for the accomplishment of the church’s total ministry (Acts of Synod 1973, pp. 62-64). It should be noted that the CRC is somewhat different in this regard from other denominations, including many Presbyterian polities, in which the offices of pastor and elder are understood to have lifetime tenure. Though most ministers of the Word are called for indefinite terms, unlike the specific terms typically used with elders and deacons—ministerial term calls are also sometimes used (Supplement, Art. 8, C). The principle of limited tenure comes to expression in our polity for ministers of the Word in that ministers are ordained for a certain role and retain their ordination only as long as they serve in a position which is “ministerial” in nature, consistent with this role.

3. The supervision of ministers of the Word

Because the ministry of the Word is a labor in and for the church, pastors exercise their office in close coordination with elders and deacons, who provide supervision and accountability as well as support and encouragement to those in the pastoral office. In distinction from other Reformed and Presbyterian polities, pastors in the CRCNA are supervised directly by a council rather than by a major assembly. This is true not only of pastors called to serve directly in a local congregation but also of those called to noncongregational service such as chaplains, professors of theology, ministers engaged in denominational work, or those serving in the growing number of other such noncongregational positions (as is clear by comparing Art. 13-a and 13-b). This local oversight of pastors places a significant responsibility on elders and deacons to understand their role in providing supervision and support as it relates to ministerial work, and this is evident in such responsibilities as the requirement of a council’s approval for release from a call (Art. 14-a; 17-a).

Synod 1978 dealt in some detail with the issue of the “ordinary” and “extraordinary” tasks of ministers of the Word (see Acts of Synod 1978, pp. 474-83). Among the key observations made to that synod was the principle that a minister of the Word is set apart by and for the church, for official tasks assigned by God to the church. While recognizing the challenge of supervising the work of noncongregational ministers at times, the study committee reminded synod of the importance of ecclesiastical oversight for all who represent the official ministry of the church (Acts of Synod 1978, pp. 477-78). This reminder is perhaps even more important today, as the church has come to accept an increasing diversity of positions in which an individual may retain official standing as a representative of the institutional church. This reality affects both those ministers who serve in noncongregational positions (Art. 12-13) as well as those who are between calls because of a release from active ministry service in a congregation or other institution (Art. 17-a).

C. New cultural realities and shifts in thinking about ministerial office

Along with an increasing diversity of ministry positions in the church, there have been many other changes in the church and in wider culture since the substantial revisions to Church Order were adopted in 1965. Some of these changes are cultural; others are specific to the life of the church or of the Christian Reformed denomination. These changes have naturally shaped the way the church views office and ordination in our present context, as noted particularly in Overture 5 (deferred from 2020): “Appoint a Study Committee to Review Church Order Articles 12-17.” We highlight several of these changes here:

1. Growing use of “business” language and expectations in church leadership

One of the most notable shifts is the application of business principles to the life of the church. This is evident in churches using the language of “hiring” or “firing” a pastor rather than “calling” an individual to serve and “releasing” an individual from his or her call. It is seen in pastors who go about a “job search” without consulting their fellow officebearers, and in “pastor job descriptions” that resemble the job descriptions of corporate officers. A business model often emerges from a kind of pragmatism or desire for efficiency on the part of both churches and pastors, and from a loss of appreciation for the spiritual nature of ecclesiastical office or a respect for the individual holding office in the church. While pragmatism and efficiency have their place, such priorities can obscure the role of God in the life of his people and thus diminish the significance of the calling to a “ministry of the Word,” and to the sometimes difficult work of laboring together as witnesses to the grace of Jesus Christ. It may also result in unrealistic or unsustainable expectations from congregations, eventually resulting in conflict between pastors and churches. While there is much the church can learn from a variety of sources, including the business world, it is important to hold to a biblically and theologically informed view of the church and of ordained ministry when in the process of calling and supervising ministers of the Word. The church is a spiritual reality shaped by different principles, driven by different goals, and assessed according to different measurements. In a business model “hiring” and “firing” are pragmatic responses to a perception about how ministry is going and may not allow room to see how God’s Spirit may be at work in prophetic ways that challenge the understanding we have of ourselves as individuals and as church communities.

2. Significant differentiation of ministry positions within and beyond the local congregation

As in many occupations, ministry has seen increasing specialization in the past several decades. Whereas it was common for churches to have only a solo pastor, it is now becoming common for churches to be served by several individuals who may each bear a title such as “Pastor of _______.” The number of noncongregational ministry positions is also expanding, with pastors serving in denominational positions, as faculty in higher-education institutions, and with other ministry organizations. This requires the church to reframe its thinking about the specific tasks of ministers even as it continues to reflect on what lies at the center of those tasks. Individuals who serve in ministry both hold an “office” (an ecclesiastical designation) and a “position” (an organizational designation).

3. Diminished longevity in any occupation or career

In today’s job environment, adults will typically change jobs a number of times in their lifetime. This reality is also reflected in the church. While once it could be assumed that ordained ministry was a call to dedicate one’s life and full-time labor to the work of the institutional church, that is no longer the case. Further, life circumstances such as a spouse’s career opportunities, a desire for further education, or the need to care for children or elderly parents can affect one’s sense of continued calling to the traditional tasks of ordained ministry in ways not envisioned several decades ago. And as the Study of Bivocationality Task Force noted, the ministerial calling is increasingly seen as one that can be fulfilled in combination with other occupations which may or may not be related to positions traditionally seen as pastoral (see Agenda for Synod 2023, pp. 294-96). Yet despite the growing number of reasons for leaving a particular congregation or ordained ministry altogether, there remains a certain stigma attached to such a departure. Our single process for separation from a specific call means that the suspicion of conflict may attach to pastors who leave any ministry role, even if conflict played no part in the decisions. We will explore this reality in more detail in section IV, B, 4, below.

4. Increased concern over ministerial “fit”

Just as pastoral ministry is becoming increasingly specialized, congregations are sensing a uniqueness in their own calling, such that pastoral calls must include increasing awareness of the particular local needs of a congregation. As individual CRC congregations increasingly see themselves as having a unique culture and set of expectations, they become more particular about their minister’s alignment with the congregation’s values. Pastor search processes take longer, and fewer opportunities exist for pastors to move to a congregation that will offer a better fit. In addition, pastors, who have become more particular themselves, are less likely to accept new calls. This situation can create a sense of impatience at times on the part of a congregation, a pastor, or both, when there is a sense of misalignment between them.

5. Anxiety from increased pace of change

The speed with which the surrounding culture moves has created in many churches a reactionary impulse to move just as quickly, diminishing the capacity to bear with one another and look prayerfully for the leading of the Holy Spirit. Churches in North America face a season of declining membership, and congregations sometimes believe that a change in pastoral leadership may be the needed catalyst for renewal or growth.

6. Decreased awareness of or appreciation for church procedures

As Overture 5 notes, “Church leadership is often undertrained in Church Order which, in times of conflict or dissatisfaction with the pastor, can result in (1) failure to use the tools Church Order provides, such as church visitors and/or the wisdom of classis and other classical functionaries, and (2) deferring instead to Pastor Church Resources [now Thrive] for a quick solution.” Sometimes assemblies and pastors opt for pragmatic solutions, perhaps in an effort to avoid conflict or avoid the awkwardness or formality prescribed by Church Order. Unfortunately, as was emphasized to our task force on several occasions by classis leaders and denominational staff, sometimes the “shortcuts”—which seem convenient at the time—result in more work later on as informal solutions lead to uncertainties about what was actually decided, or how to implement agreements concluded upon assumptions rather than clear decisions. As one denominational staff member observed, “In a world full of devices and apps, we need to resist the temptation to find quick fixes that allow us to bypass the hard work of discernment and discipleship that’s done as we seek the Spirit’s guidance in messy community.” It is important to recognize that Church Order, similarly, cannot provide a “quick fix.” Rather, it offers a framework for doing the kind of discernment and discipleship necessary to identify ways in which God’s Spirit may be working in a particular situation.

7. Increasing ethnic and cultural diversity within the denomination

CRC theology and ecclesiology are heavily shaped by Reformed thinking that has emerged from a Dutch-American and Dutch-Canadian context. Nevertheless, our community of faith is not identical to that of the generations before us. All facets of our church life and identity have changed and are changing, from theological understanding, biblical interpretation, and mandates in Church Order, to cultural and societal values that call us to faithful witness in the world. Some find that the CRC they know from the past is not the CRC they are experiencing in the present. Likewise, we have become more diverse as God has enfolded people from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and congregations in new geographic regions, into the Christian Reformed Church. Such diversity, from the past to the present and across ethnic and cultural contexts, results in diversity of thought and practice, and all of this changes the cultural context for CRC congregations as well as for the denomination as a whole.

Beyond the simplistic generalization of Western individual rights versus Eastern communal responsibilities, within various cultures there are different emphases on law and guilt versus interpersonal relationships, democratic egalitarianism versus hierarchical structures, and leaders’ authority versus servanthood, to name but a few. With this in mind, we want to note that the application of the Church Order should take cultural context into consideration, and the processes should be held loosely in any particular situation rather than tightly across all situations. Our structures of accountability are important, but these should not be reduced to the confines of paperwork and reports. As followers of Christ, we commit to live out an accountability that is marked by a posture of “one another” and the productive stewardship of relationships. The values articulated in the 1996 synodical report that is now published as God’s Diverse and Unified Family (see crcna.org/sites/default/files/diversefamily.pdf; Acts of Synod 1996, pp. 510-515, 595-619) provide a helpful framework for living out this call in the application of Church Order to an increasingly diverse number of situations in the CRC today.

Conclusion

We want to emphasize that a number of these shifting realities are not, in and of themselves, either good or bad. They are simply changes that we need to be aware of because they affect our understanding about the relationship between Christ’s church and the world today and thus also affect the way we think about the nature of ministry and leadership in and for the church. In the next two sections of this report we will identify some of the ways these cultural changes may call us to rethink the practical workings of Church Order in relation to the supervision of ministers and releases from calls. Again, our desire in this process is not simply to create different procedures but to recognize these procedures as tools to help pastors, churches, and assemblies feel a deep sense of connection and belonging as we collectively discern how to serve faithfully in the CRC.

D. Methodology

As our task force began its work, we spent a significant amount of time reviewing classis and denominational records in order to understand the current landscape of ministry in the CRCNA as it relates to matters addressed in Articles 12-17. In addition, the task force requested feedback from the stated clerks through an online survey and through an in-person discussion at the stated clerks’ conference in January 2023. Hearing stories was a necessary part of our process; we solicited these through our networks. Direct feedback and stories came from individuals via emails, conversations, denominational representatives, and classis contacts.

Because the topics covered in this report affect specific groups of individuals, the task force also consulted with denominational leaders with experience in the areas of chaplaincy (Tim Rietkerk) and diversity (Reginald Smith). We corresponded with the leadership of Resonate Global Mission with regard to its understanding about how calls to missions should be processed, with ethnic ministry leaders from various non-Anglo communities across the CRC, with denominational Human Resources personnel in both the U.S. and Canada regarding employment best practices, and with the Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations Committee concerning implications of changes proposed to the present Church Order Article 13-c. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions they have made to this report, as well as the input of all who shared stories of ministry from which we could learn.

Finally, the task force looked at a significant amount of data from classis minutes, from the CRCNA Yearbook, and from the Acts of Synod to help us understand trends related to noncongregational ministries and the frequency with which classes address specific requests related to Articles 12-17 of the Church Order. Relevant findings will be reported at appropriate points as they affect the recommendations presented later in this report. The task force is thankful for the work of the Yearbook staff and other denominational employees for their assistance in collecting the data relevant to our discussions.

III. Accountability and supervision

A. Background and theological observations

As noted in the introduction, one key area of our task force’s mandate involves the calling, supervision, and support of pastors serving in settings outside a local CRC congregation. Within this area of focus, we will first explore the subject of calling (Art. 12) and then move on to issues of accountability and support (Art. 13).

The CRC’s understanding of all ministry is rooted in the perspective described in section II of this report: ordained ministry recognizes both the call to serve the risen Lord and the responsibility to represent that risen Lord in a position of trust and authority. Since the time of the Synod of Dort (1618-1619), Reformed churches have recognized a legitimate place for ministry in settings other than the local congregation. However, the CRC has always experienced a certain tension about such positions, as it has sought to discern which positions should be deemed “ministerial” and how to apply such discernment to changing cultural situations.

The historic tension in the CRC over what has been called “extraordinary” ministry is evident in past reports to synod (see Agenda for Synod 1930, pp. 30-49; Acts of Synod 1950, pp. 322-43; Acts of Synod 1961, pp. 233-52; Acts of Synod 1978, pp. 474-83). These reports provide helpful background for our present work and thinking on these matters.

1. Calling ministers to serve in noncongregational settings (Art. 12)

- The nature of ordained ministry

Church Order Article 12 addresses the specific tasks and callings of a minister of the Word. Article 12-a describes the tasks of a minister in a CRC congregation, which has historically been the work of most CRC ministers: to “preach the Word, administer the sacraments, conduct public worship services, catechize the youth,” and other similar responsibilities. Exceptions were granted for ministers serving in the work of missions, in denominational leadership, or in chaplaincy positions deemed clearly “ecclesiastical”—generally these positions were, by definition, “extraordinary” and their ministerial character was undefined. As a result, synod heard recurrent concerns about the consistency of the standards applied to determine what work was, indeed, genuinely “ministerial” (see Acts of Synod 1950, p. 324; Acts of Synod 1961, p. 56).

When it adopted the present reading of Articles 11-12, Synod 1978 helpfully observed that the CRC recognizes only one class of ministers. What distinguishes pastors of congregations from other ministers is not their call to minister the Word but rather the setting (either the local congregation, or some other setting) and the specific tasks (either general congregational ministry, or some “specialized” work applying the message of the Word to the world). Synod 1978 therefore abandoned the traditional language requiring that positions outside the local CRC congregation be “spiritual in character and directly related to the ministerial calling,” and concentrated instead on attempting to ensure that “each approved ministry position will be in fact a meaningful and appropriate expression of the essential nature (purpose and primary task) of the ministry of the Word” (Acts of Synod 1978, p. 479). This shift in language provides a helpful starting point for our own current reflections on ways to connect ministry outside the local congregation to the work of the wider church.

One recurrent emphasis in the discussions of synod has been the expectation that fields of labor beyond the local church still require a formal call from and accountability to “the church as an organization” through a local consistory [now council] (Acts of Synod 1978, pp. 477-78; cf. Acts of Synod 1950, p. 61; Acts of Synod 1961, p. 58). We note that this is different from the practice in other Reformed and Presbyterian denominations, which place the supervision of pastors at the classis level. Because this issue needs further definition, we will return to it below (see section III, C, 1). - Two categories of “extraordinary” positions

Synod has been hesitant to identify all of the specific types of positions in which a pastor may serve beyond the local congregation in an ordained capacity, preferring to leave such decisions to the classis. There are, however, some positions that synod has granted blanket endorsement. As such, synod has developed two basic categories of noncongregational service: those which have prior synodical endorsement (Art. 12-b), and those which require the classis to judge the merits of the position’s connection to ordained ministry (Art. 12-c). This distinction first originated in 1947, when synod approved the position of radio minister as being ministerial and subsequently determined that its ruling applied retroactively to other synodically appointed positions and to missionaries; later, chaplains and specialized transitional ministers were also added (Acts of Synod 1947, pp. 21, 59-60, 71; see also Acts of Synod 1961, pp. 249-53 and section III, B, 7 below). All other positions are covered in Article 12-c and require a specific declaration from the classis, with the concurrence of synodical deputies, that the position being filled “is consistent with the calling of a minister of the Word '' and is in keeping with other synodical requirements. - Limitations on approval of ministry positions outside a congregation

Ordained ministry must be focused on the Word and sacraments (Art. 11); as an earlier synodical report puts it, such ministry has a focus on the “welfare of the church” rather than on the welfare of another institution (Acts of Synod 1961, p. 248; cf. Acts of Synod 1978, p. 477). At the same time, the growth of bivocational (or multivocational) ministry makes clear that ordination as a minister of the Word does not require that a pastor be focused only on the welfare of the church or on the Word and sacraments. But this understanding does provide at least a helpful starting point for evaluating a new request for a “noncongregational” position. It is further worth noting that Article 12-c expects that a vacancy in such a position will lead to a review by classis and the synodical deputies before another call to that position is issued (current Supplement, Art. 12-c, a, 4). - Ministers serving on loan

The current Article 13-c was added to the Church Order in 1976. The study committee reporting to that synod (see Acts of Synod 1976, pp. 32-34, 497-517) noted that while there is overlap among ministers serving on loan to non-CRC congregations and ministers serving the CRC in noncongregational positions, the question for those on loan is consistency with the work of a CRC minister rather than consistency with the work of a minister in general. We would note that this category of pastors serving on loan is also similar to, but distinct from, that governed by provisions for the “Orderly Exchange of Ordained Ministers,” which allows CRC pastors to receive calls to RCA congregations (cf. Supplement, Art. 8, D).

Synod agreed that such loans to other denominations could be consistent with CRC ministry, but with the stipulation that these provisions are temporary and serve the cause of a Reformed witness in the context of the non-CRC congregation (Acts of Synod 1976, pp. 510-11). Put simply, the CRC did not intend to train and ordain ministers or to supervise pastors’ work in positions in other denominations, and synod thus attempted to put specific criteria in place to ensure that the loaning of pastors to churches outside the CRC did not become a general practice. The challenges of enforcing this latter provision is a subject to which we will return below (see section III, C, 4).

Summary

The issues noted here indicate the basic understandings of the nature of called ministry positions in the CRC. While the nature of ecclesiastical office involves service to the Lord, ordination also confers a representative function on those who serve in ecclesiastical offices. Ministers of the Word visibly represent and speak for the institutional church. Thus ordination requires some kind of significant connection to the gospel witness of the wider denomination. This reality will affect the way councils and classes discern whether a particular position fits our denominational understanding of the ministry of the Word, and will affect the nature of supervision for such positions.

2. The nature of supervision (Art. 13)

Ministers of the Word are required to submit themselves to continuing supervision as they carry out their work. As observed in section II of this report, ordained servants in the church are not simply “free agents” but representatives of the church whose position therefore requires them to be in contact with other church leaders who can encourage, support, and supervise them in their service to the Lord. Article 13 identifies some key principles that guide the outworking of this supervision:

- Accountable to the local council

One key element of the CRC view of ministers in noncongregational positions is the recognition that they remain under the supervision of the local council. Article 13-a summarizes the supervisory arrangements of pastors in congregational settings by noting that such pastors are “directly accountable to the calling church, and therefore shall be supervised in life, doctrine, and duties by that church.” With the exception of supervising duties, this summarizes the CRC’s view of all noncongregational pastors as well: each minister of the Word is accountable to, and supervised by, the council of the local church, which has “primary responsibility” for overseeing the minister’s doctrine and life (Art. 13-b). - For the ministry of the Word

Recalling that Article 11 governs this whole section of the Church Order, we could say that the council is regularly to consider how a pastor’s work of proclaiming, explaining, and applying Holy Scripture fulfills the ministerial calling to “gather in and equip the members so that the church of Jesus Christ may be built up.” As we have noted before, the ministry of the Word is central to the calling of this office: while all Christians are to be people of the Word, there is a particular responsibility of ministers to live and work in a way that allows the Word of God to be displayed at the center of their vocation. - Joint supervision

The current Articles 13-b and 13-c address the situation of pastors whose position is not in a local CRC congregation and is therefore subject to the authority of more than one body. The supervising organization may be a denominational agency, an educational institution, a hospital, the military, a corporation, or another congregation. In all of these cases, Church Order and synodical regulations distinguish between supervision of life and doctrine, which remains with a local CRC council, and supervision of duties, which is exercised by the “partner(s) in supervision” (see Supplement, Art. 13-b). This distinction means that ecclesiastical discipline remains the responsibility of the council. While the current Church Order Supplement only notes this disciplinary responsibility in the section of the Supplement describing the joint supervision of pastors on loan to other denominations (Supplement, Art. 13-c, f), the principle is implied in all joint-supervision arrangements. - Continued adherence to CRC doctrine and polity

We list this consideration separately in order to call particular attention to it. Though this expectation is currently only spelled out in regard to ministers serving on loan (Supplement, Art. 13-c, c), the CRC clearly expects all its officebearers to adhere to the doctrine and polity commitments of the denomination as indicated by their commitment to the Covenant for Officebearers (Art. 5). Missionaries, chaplains, and other CRC ministers who serve outside a local CRC congregation are no less bound to these commitments than are congregational pastors or those serving on loan. - “Proper support”

The CRC expects that councils shall attend to the “proper support” of the work of ministers of the Word (Art. 15). While this is not, strictly speaking, a matter of accountability, it is a matter that speaks to the relationship between the pastor and the council of the calling church. Again, these issues are not covered directly by the Church Order but are implied in portions of the Supplement that address participation in the Christian Reformed Church ministers’ pension plan and other benefits (e.g., see Supplement, Art. 13-c, g; and Supplement, Art. 15). In the past, synod has recognized that salary and benefits support for ordained clergy are the primary responsibility of the employing organization (Acts of Synod 1969, p. 48; Acts of Synod 2004, pp. 622-23; Acts of Synod 2005, pp. 742-43). Thus the calling church’s main duty in the matter of “proper support” is to work with the ministers it calls to ensure that the matters addressed in Article 15 and its Supplement have been sufficiently addressed in the calling process (see also Acts of Synod 2023, pp. 963-64).

It should be noted, however, that the support of ministers of the Word is not just a matter of salary and benefits. For this reason we encourage congregations to consider ways to support the work of noncongregational ministers through prayer and other relational support (see section III, C, 6 below).

Conclusions

Articles 12 and 13 identify a number of important principles for the calling and supervision of ministers of the Word in the CRC, and in particular in how the local church is called to support and oversee the work of pastors not in the direct service of a CRC congregation. However, as we shall see, the context in which calling and supervision occur today has continued to grow in complexity and scope. Thus it is important to note the principles we have identified above as we consider particular questions that arise in the present context.

B. Issues and Observations

The cultural realities and changes in thinking about the ministerial office (mentioned in the opening section of this report) present a number of issues and questions about the supervision and accountability of pastors.

1. Growth in the number and variety of “other called positions”

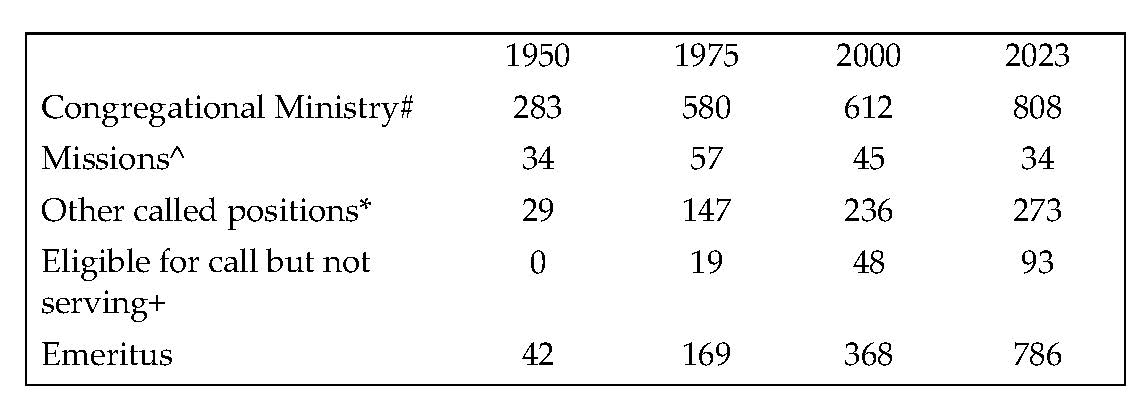

In 1950 the vast majority of pastors in the CRC served in a congregational setting. As the chart below indicates, the number of CRC pastors serving in “other called positions” increased dramatically between 1950 and 1975, and that number has continued to grow (though not as significantly, particularly as a percentage) in the years since. This increase appears somewhat less significant when considering a roughly corresponding decrease in the percentage of CRC pastors serving in world missions, but the rise still indicates an expansion of the areas in which CRC ministers serve. The CRC has a significant number of active pastors ordained as chaplains (almost 9%) and a roughly similar number serving as professors, administrators of Christian organizations, or ministers on loan to congregations outside the CRC (about 3% in each of these categories).

#This number includes church planters whose credentials are held by another church.

^Numbers for 1950 include home missionaries without a set charge.

*This includes chaplains, educators, denominational personnel, and other similar positions.

+This largely includes those who are eligible for call via Article 17 but not actively serving in a called ministry position.

(Source: CRC Yearbook for years shown)

When combining the numbers of missionaries and of pastors who have no call with the number of “other called positions,” the result is that almost a third of all active (not retired) CRC pastors have their primary responsibility outside the ministry of a local congregation. (This does not take into account those serving in such positions as commissioned pastors.) This dramatic shift means that some questions that have long accompanied our understanding of ordained ministry, and how such positions are related to the local church, have now come to the fore in new ways. The sheer number of “other called positions” also means that local congregations are faced with both the challenge and the opportunity of determining how best to provide accountability and encouragement for the significant number of pastors whose ministry may not be readily visible to the local congregation.

Our task force identified a number of positions for which a significant portion of the responsibilities are supervised outside of a local CRC congregation, while the official responsibility for doctrine and life remains with the council:

- Chaplains

—Military, hospital, or workplace chaplains (Art. 12-b)

—Other institutional chaplains (Art. 12-c) - Pastors serving congregations other than the CRC congregation that holds their credentials

—Missionaries (Art. 12-b or 12-c)

—Church planters (Art. 38-a)

—Serving churches in the RCA (Art. 8)

—On loan to other denominations (current Art. 13-c)

—Specialized transitional ministers (Art. 12-b)

—Pastors serving two congregations (either within or outside the CRC)

—Interim pastors (often retired or sometimes between calls, cf. Art. 17 or 18) - Pastors serving in educational settings

—Theology professors at Calvin Theological Seminary (Art. 12-b)

—Theology professors at other institutions (Art. 12-c)

—Christian school teachers (Art. 12-c)

—University campus ministry leaders (Art. 12-c) - Pastors working in administrative settings

—Denominational employees (Art. 12-b or 12-c)

—Employees of other nonprofit organizations (Art. 12-c) - Bivocational pastors (proposed Supplement, Art. 15, Guideline 3)

- Pastors without a current call

—Released from a congregation (Art. 17)

—Term call concluded (Art. 8) - Retired pastors (Art. 18)

(For a representative list of specific positions approved over the years, see the Index of Synodical Decisions 1857-2000, pp. 404-10.)