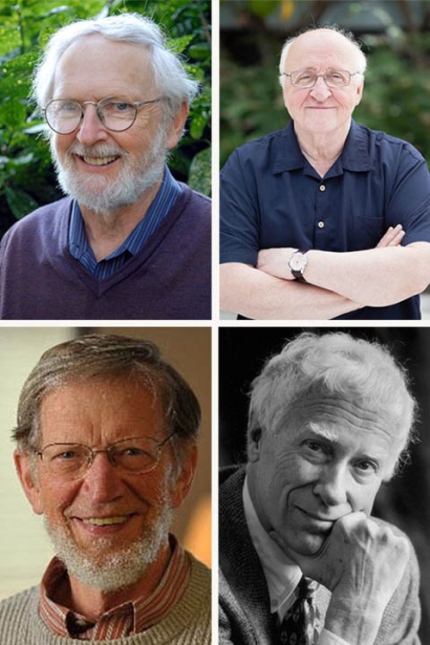

Four Renowned Professors Return for January Series 2016

George Marsden (top left), Richard Mouw (top right), Alvin Plantinga (bottom left), and Nick Wolterstorff

In his introduction, Michael LeRoy, president of Calvin College, referred to them as “the Beatles” — academic superstars who returned to Calvin on Thursday to speak at the January Series 2016.

The four former Calvin College professors — three philosophers and a historian — have written prize-winning books, published well-respected scholarly articles, and taught and spoken at prestigious universities in North America and abroad.

Addressing the topic “The Renaissance of Christian Thought,” philosophers Nicholas Wolterstorff, Richard Mouw, and Alvin Plantinga and historian George Marsden each had a few minutes to sketch ideas and movements that have helped to shape their careers.

They also spoke of how these ideas and movements have touched and transformed Calvin College from an insular institution in the 1950s into the respected liberal arts college that it is today.

“There has been a remarkable renaissance of Christian thought that has taken place over the last 50 years, and Calvin has played a role in it,” said Wolterstorff, the Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale University. He taught at Calvin from 1959-1989.

When he came to Calvin as a student in the 1950s, said Wolterstorff, Christian philosophy was not a recognized academic discipline.

But the solid grounding in the Reformed faith he got at Calvin gave him a hand in helping to change that.

“At Calvin, I got a gripping vision of being a Christian philosopher from my teachers,” he said.

Teachers such Harry Jellema and Henry Stob, he said, offered the “idea of faith seeking understanding, of looking at philosophy through the eyes of faith . . .There was no index of forbidden books. We were asked to engage and learn from the entire Christian heritage.”

When Wolterstorff was in graduate school, there was little writing in the field of philosophy that was recognizably Christian.

But that began to change as the field grew, he said. During his years at Calvin, Wolterstorff and other members of the philosophy faculty would meet once a week to discuss and critique papers they had written on Christian philosophy.

“We would meet for two hours and go over a paper page by page. You could call it tough love,” said Wolterstorff, who is especially recognized for his work in Christian aesthetics, the branch of philosophy that deals with the principles of beauty and artistic taste.

“Calvin is where I and others learned to be Christian philosophers,” said Wolterstorff.

Alvin Plantinga, who taught philosophy at Calvin before moving on to the University of Notre Dame, was another pioneer in the field of Christian philosophy. He is best known for his work that justifies belief in God without external evidence.

“When I began in the field, if you were addressing issues of faith, you were told you were doing theology and not philosophy,” he said.

“But there were those of us who wondered, ‘Why can’t there be something that is explicitly Christian, a science that starts from Christian ideas?’”

He said he and Wolterstorff and other philosophers asked such questions as “Why can’t we take for granted the main lines of the Christian story as we do our work?”

Later, in a question and answer session, Plantinga said, “If the Christian story is correct, and I believe it is correct, it is the most wonderful thing in the world.”

Richard Mouw, who taught philosophy at Calvin from 1968-1985, served for 20 years as president of Fuller Theological Seminary. He now fills the position of Professor of Faith and Public Life at Fuller.

Mouw said “it was a dream come true” when he was hired at Calvin, where he was able to discuss and teach the significance of linking Christian philosophy with bringing God’s justice into all areas of life.

Calvin was a place where he found “a robust evangelicalism that embraced the saving grace of the sovereign God” and addressed such social issues as poverty and racism.

“I was able to take what I learned here at Calvin into new areas of service,” he said. “All of us here today went out with a sense of mission into other important academic settings.”

In his work Mouw has been a leader in interfaith theological conversations, particularly with Mormons and Jewish groups. He served for several years as co-chair of the official Roman Catholic-Reformed dialogue.

Author of an award-winning biography about Puritan preacher Jonathan Edwards, George Marsden taught history at Calvin from 1968 to 1985 before going on to Duke University and Notre Dame. He has now returned to Calvin as a scholar in residence.

Marsden said that when he was a college student in the 1950s, evangelicalism was tied closely to — if not synonymous with — the fundamentalism of the time.

But things started to change as the evangelical movement began to grow and its members became more engaged with the broader society.

“Various forces were at work that led to evangelicalism becoming the most vital religious community in the last several decades while other groups have declined,” he said.

The movement grew, at Calvin and elsewhere, as people began to leave behind the fundamentalist view of their Christian faith and engaged with the wider issues of the day, said Marsden.

“At Calvin, we have been shaped by a great Reformed tradition. We have done our homework, have honed our ideas, and have been able to articulate our positions,” he said.