Seeking Communion with God

Cornelius Plantinga has followed the same rhythm of prayer for many years, setting aside time in the morning after he wakes up and again at night before going to sleep to speak to God in a number of ways.

Sometimes he prays in joyful expectation as he looks forward to what he has coming up that day; other times, after a rough day, his mood might be cloudy and his words express some irritation. On some occasions he also speaks to God about the Lord’s sovereignty over a diverse and amazing creation.

But always as he prays, it is never to a single listener but to the triune God — a society of three, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. At times, Plantinga’s words and prayers expand to take in the heavenly hosts, and, beyond that, he may find himself including many loved ones who have passed away.

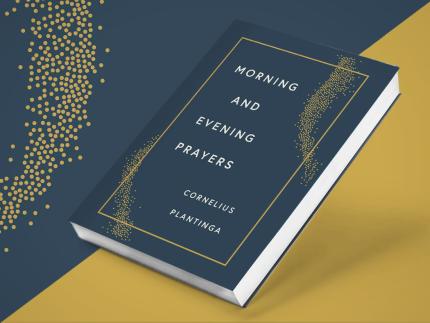

“We pray into a heavenly society as imagebearers of God. I think about this every time I pray,” said Plantinga in a question and answer session about his new book Morning and Evening Prayers, which offers prayers for people to consider praying every day for 30 days — and then, if they are so inclined, to move back through them again.

Plantinga, the former president of Calvin Theological Seminary, has listened to hundreds of prayers recited by others over the years; has turned to the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer with frequency to pray, and has literary prayer mentors to whom he turns — persons such as John Baillie, a professor and theologian whose book A Diary of Private Prayer has been a help and guide for many seeking prayers to pray since it was published in 1936.

“For many years I’ve been moved by other people’s prayers, by the psalms, by the prayers of Paul, and by the prayer Jesus taught us to pray,” said Plantinga in the interview conducted on Zoom by Noel Snyder, program manager at the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship (CICW).

In an interview for an Eerdmans publicity release, he added, “Other people’s prayers jog me out of my rut. I use them to ask for things I hadn’t thought to ask for. I thank God for things I had entirely overlooked. I intercede for some kinds of people I had lamentably ignored. On the spot, my prayer life expands.”

Over the years, Plantinga said, he has been asked to pray during a church service and will think through, as carefully as time permits, what to pray. On occasion, he has also written out prayers that he has been asked to offer for special occasions.

Then a year or so ago, John Witvliet, president of CICW, suggested that he write a book of prayers. An author of many books, Plantinga took on the task without having to think too much about it. Basically he delved right in, finding it to be “a spiritually significant project,” he said.

Modeled after his own life of prayer, the words flowed; sentence led to sentence; various images struck him; and he felt himself move into a sacred space, illuminated by the same Spirit to whom he prays.

As he wrote, he said, he kept in mind — as he always does in prayer — the many things going on in the world that must be included in the prayers he prays. His mind, he said, must be open and alert, keenly aware of the joys and sorrows of the life going on among us.

Meanwhile, he said, he believes God wants to hear not only about the big things but also about the minor occurrences of any given day and time.

“I’m not sure how it works, but I do have a sense of God listening and that he is willing to grant prayers he deems to be wise. He listens and is a careful judge of what we pray,” said Plantinga.

As he wrote the prayers for the book, he said, he thought with regularity of the two billion or so Christians in the world and how at any given time he was part “of a great praying fellowship seeking communion with God.”

He also often has his mental radar out for such soft and subtle things as flowers in bloom, the sounds of laughter, the sense of new seasons in the air. But then there is also the plight of the homeless; the unemployed; people suffering from the COVID-19 virus. All of this — in one way or another — Plantinga seeks to incorporate in prayer.

Some of the prayers are praises, for instance, for the garbage collector who treads softly, seeking to muffle the noise of his truck mashing trash in the early morning as people in a neighborhood sleep. “It’s not wrong to notice those little things. If you are alert to beauty, to good work, your own life is enhanced,” said Plantinga.

In one morning prayer he writes: “To you loving God, I bring thanks for your abiding presence. . . . Listening God, I speak to you this morning with simple trust. . . . We want to be weavers, O God. Teach us to weave together our work and witness into a seamless garment that warms others and that shows forth your beauty in the world.”

In an evening prayer he writes: “What surprises me is faith. Before I sleep tonight, I want to say to you how remarkable it is that so many of us believe. . . .”

And in another prayer for morning: “Give me resonance, O God, with others around me. If my life feels like a song today, teach me to weep with those who weep. If today I feel strung tight or restless, walled in by loneliness or regret, bring me freedom to rejoice with all your children who rejoice.”

And in another for evening: “Loving God, you are worthy of praise in a thousand tongues. Let English and French tongues praise you tonight. Let Dutch and Hungarian tongues praise you. Let Brazilian and Honduran tongues praise you. . . . Let all people on earth praise you and magnify your name in their own language.”

Gratitude in prayer is a great blessing in itself; it lifts us up; it focuses us on things that can make life sweet rather than make us groan.

“If you find things to be grateful for in an otherwise dreary situation,” Plantinga said, “you will do a lot better in life.”

Being able to praise God is a great gift; it allows us to express all of who we are to the one who has made us; it can show our dependence on the one who knows all; it also helps us, he said, in some mysterious way, come to know the unknowable God better.

Plantinga’s prayers move from the mournful to the merry and merciful; they are literate and well thought out; they are prayers we can all pray with a full range of emotions; they are prayers that can touch us in our souls and help us to express the experiences we have of God.

“Prayer is not only right and fitting and appropriate, but it is also formative,” said Plantinga. “When we pray and praise and lament and petition, we are molding ourselves more fully into being children of God.”