Lessons Learned from Sankofa

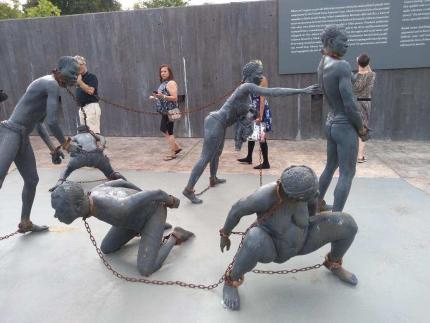

A sculpture at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice

Jerome Burton

On a journey to visit civil rights sites in the U.S. South, Sankofa participants had just left a tour of the museum at the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King, Jr., was shot by James Earl Ray and later died on Apr. 4, 1968.

On impulse, they decided to check out the nearby Mason Temple Church of God in Christ. It was not on the formal tour, so they assumed they wouldn’t be able to get into the church in which King had given his last public address, said Reggie Smith, director of the Christian Reformed Church Office of Race Relations and the Office of Social Justice.

“Going there (to Mason Temple) had always been on my bucket list,” said Smith, one of the coordinators of the Sankofa trip, which matched 24 African Americans with 24 white persons or persons of another ethnicity to ride on a bus to visit places of historic significance. The trip was sponsored by Race Relations, Calvin Seminary and CORR (Congregational Organizing for Racial Reconciliation.)

Sankofa is a word from Ghana that basically means “looking back [at our history] in order to go forward” and address matters of social justice.

As their bus pulled up to the Mason Temple, the headquarters of the Church of God in Christ, the largest Pentecostal denomination in the U.S., they saw a security guard. And when they explained their reasons for visiting, the guard was more than willing to let them into the church building, said Smith.

“We were all able to walk around and soak up the history — and we had the special chance to listen to two people who had come along on the trip. They had been living in Memphis at the time King was killed,” said Smith.

The couple, George and Bertha Jefferies — members of St. Phillips AME in Grand Rapids, Mich. — spoke of the night on which King had talked at Mason Temple. Bertha even pointed out where she was sitting on the evening of Apr. 3, 1968, as King spoke.

She explained that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's Rev. Ralph Abernathy, King's associate, was slated to be the evening speaker, but the 3,000-person crowd wanted to hear King. Abernathy phoned King at his room in the Lorraine Motel and asked him to address the assembly.

King came and spoke, providing support for the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike that had drawn him and other civil rights leaders to Memphis. He called for nonviolent protests in the fight for economic justice. King’s remarks that night would become known as his “Mountaintop” speech.

During the visit to the church, Smith said, he couldn’t resist climbing into the pulpit and giving King’s speech by heart. He preached King’s powerful words, calling on the people of Memphis to march in support of the sanitation workers.

And at the end, he said from memory: “We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. . . . I just want to do God's will. And he's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”

The three-day Sankofa trip made its first stop in Ferguson, Mo., to visit the place where Michael Brown, a young black man, was shot and killed by police on Aug. 9, 2014. A light pole near where his body lay is decorated with memorabilia, drawing attention to the death that led to protests nationwide and beyond and helped to spark the Black Lives Matter movement. A plaque and a bronze dove dedicated to Brown is installed in the sidewalk near where he was fatally shot.

Viewing the place where Brown was killed made Andrew Oppong, who grew up in Ghana, think of how the bodies of black people are not respected and have so often been subject to violence, he said.

“The black body is still a threat,” said Oppong, a justice mobilization specialist for the Office of Social Justice. “Visiting there and other places on the trip, like the lynching museum, convinced me more than ever of the need to dismantle institutional racism, to call it out when we see it.”

Commonly referred to as the lynching museum, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is set on six acres in Montgomery, Ala. The site includes a memorial that symbolizes thousands of lynching victims in the United States and notes the counties and states where they took place.

Many of the Sankofa trip participants, like Oppong, were deeply troubled when they walked through the memorial, which contains more than 800 steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where lynchings took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns.

Among the pieces of information that struck Oppong was that many lynchings took place in town squares on Sunday afternoons. “Lynching was entertainment after you dressed up and went to church to praise God,” he said.

“History shows how the church has often been on the wrong side of justice. I know that that is changing in the CRC and elsewhere, but there is a lot that still hasn’t changed.”

Reggie Smith said he too was deeply affected as he walked through the memorial, particularly when he saw the steel column for Noxubee County, Miss., where his parents and many relatives had grown up.

He counted the names of 10 persons who had been lynched, and that caused him to ask some hard questions, he said. “I thought I could be related to some of them,” said Smith. “The experience was raw, profound, and necessary. Going through there, it felt like we were walking on holy ground.”

Andrew Rienstra-Ehlers, who works as a volunteer coordinator for World Renew, especially recalled walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., with Jerome Burton, pastor of Coit Community CRC in Grand Rapids.

On March 7, 1965, armed police, many on horseback, confronted and beat voting-rights marchers who were crossing the bridge on their way to Montgomery, the state capital. The day has become known as “Bloody Sunday.”

“Pastor Jerome grew up in Selma and was a wealth of information. He lived through some of that history. He recalled white college students coming down to work on voting rights,” he said.

Rienstra-Ehlers said he returned from the trip asking how he can work even harder to make sure oppression and racism can be eradicated from the church. “Going on the trip helped me begin to understand how others see the world and what has been done to them,” he said. “In order to grow, it is necessary to experience things such as the Sankofa trip. I hope others in the CRC go on the next one.”

Caleb Lagerwey, a history teacher at Holland Christian High School, took the trip for a practical reason — to learn about the African American civil rights struggle so that he can pass along to his students what he discovered. But he gained so much more, he said, especially from the African American man with whom he was paired.

“He has lived a life very different from mine, and that helped to give me a new perspective.”

Lagerwey learned that his partner grew up poor and without the presence of his father in Grand Rapids, didn’t finish high school, joined the U.S. Army, fought in Afghanistan and Iraq, and came out of the service suffering effects of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. He currently is trying to study for the ministry.

“Going to the places where we went was very useful. It was important to listen to others to understand more about the effects and causes of racism,” said Lagerwey. “I returned thinking about systems and how they intersect with power.”

David Koll, director of the CRC’s Candidacy Committee, found many of the stops on the trip to be valuable in helping him better understand the history of the civil-rights struggle.

For example, he said, he appreciated the chance to visit the grave of Dred Scott, the central figure in the 1857 "Dred Scott" Supreme Court case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that Scott, as an African American, was not a United States citizen and had no right to sue for his freedom.

Koll was also fascinated and troubled by the time spent at the Lorraine Museum, which in many ways has frozen in time the location where King was assassinated. This includes the place where King was shot on the second-floor balcony of the motel and the room in a boarding house across the street from which James Earl Ray looked down the scope of his rifle and pulled the trigger.

Also, said Koll, there was the chance to take part in rousing worship at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., where four small girls were killed in 1963 by a bomb planted by the Ku Klux Klan.

Connected to this, he said, was the opportunity to spend two hours with Carolyn Maull McKinstry, author of the book While the World Watched, a firsthand account of her childhood experience at 16th Street Baptist Church on the day her friends were killed in that bombing.

Reflecting on what he brought back from the trip, Calvin Theological Seminary student David Shao, who is Chinese, said he not only learned of the “heavy history of African Americans in this land, but also thought a lot about how the Chinese church and society can learn from this part of history.”

Shao may well have spoken for many on the trip when he commented: “Unreflected and unexamined history will repeat again and again. I also have a deeper and fuller sense of what the gospel can be like. The theme of exodus and liberation in this life have been close to me through this trip. I hope more people can go and benefit from it.”