Dismantling Racism Starts with the Human Heart

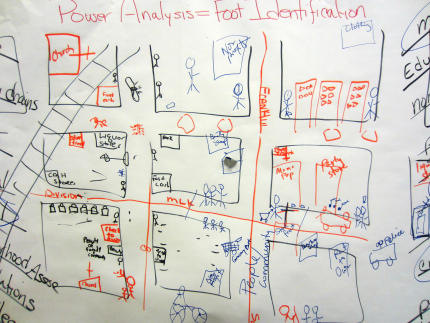

Drawing shows how racism impacts a neighborhood

Chris Meehan

The drawing displayed in the front of the classroom at Church of the Servant in Grand Rapids, Mich. illustrated the economic and social sin of racism.

What the drawing lacked in artistic quality, it more than made up for in its stark depiction of how racism can trap and define a community.

Stick-figure houses, scribbled images of police cars roaming the neighborhood, young men hanging out on street corners, a ramshackle liquor store, boarded-up businesses, and rusty railroad tracks were all represented in the picture.

Shown here was a closed community; a community of little upward mobility or movement out.

“Where does being a Christian call white people to be in all of this? What does God's kingdom look like? Does it look like this?" asked Laura Carpenter, pointing to the picture shown on an easel.

Carpenter was speaking during one of the opening sessions of a recent, three-day anti-racism training workshop put on by Congregational Organizing for Racial Reconciliation (CORR).

Churches attending the seminar included Madison Square Christian Reformed Church, Church of the Servant CRC, Plymouth Heights CRC, and Coit Community Church. Other ministries and Potters House Christian School were also there.

As a part-time pastor at Coit church, I attended the workshop. I was also there as a reporter, taking notes so that I could write this story.

“We are here to develop and share a common analysis of the Christian understanding of what racism is, how it affects people and how it applies to institutions," Carpenter said.

The workshop was geared to help white participants see the impact of racism on African Americans and other persons who are not of the dominant culture.

It was also held to give African-Americans and others an analysis of what racism has done to them, as well as how their white brothers and sisters understand racism.

In addition, the workshop gave participants an opportunity to discuss how racism has played out in their lives.

An African-American pastor said he was at his church one day when a man appeared to do some work and asked him if he was the janitor.

One man who is involved in a hip hop ministry recounted how police have stopped him several times, asking for his identification and where he was going, simply because of how he looks and dresses.

Kyle Lim, marketing and fundraising coordinator for a Grand Rapids ministry, opened Saturday morning by talking about the challenges he faces living as a young man, who is half Chinese, in the United States.

"There is something fundamentally different about my identity compared to other white folks," he said. "There is this descriptive narrative telling us that some people are better than others, and this is tied to race.

"Here in America it feels like to be 'fearfully and wonderfully made' (as it says in the Bible) means you have to be white."

Modeled after an existing program, CORR began in the 1990s at the request of denominational officials. Since then, many churches and other organizations mostly in West Michigan have attended the training.

In the mid-2000s, the Office of Race Relations of the CRC began its program called the Dance of Racial Reconciliation in the US and Widening the Circle in Canada. I have attended the Dance of Racial Reconciliation.

Racism, both of the trainings taught me, is rooted deeply in just about all aspects of our society.

"All of our institutions — the government, education, economic, even religious — have developed over the years and have been made with white people in mind," said Stacia Hoeksema, another of the facilitators, during one of the sessions.

"Racism was invented to maintain white power and privilege for white society and the fallout has been the oppression of African-Americans."

As a white man, some of this was hard to hear and seemed unfair, given that I've never been in a position of power from which I could dictate the direction our society’s institutions should take.

But an exercise called "The Walk of White Privilege" helped to drive home an important lesson.

For this, we lined up against the wall and took a step forward when we could answer "yes" to questions posed by a CRC pastor. The questions basically revolved around our access to housing, schooling, employment, and various services.

When the pastor had finished, those of us who were in the lead were asked to turn to see who was behind us. All of the African American participants were way back, some having hardly stepped beyond the wall at all.

Looking at them, I felt really sad, thinking how trapped they were by circumstances in their lives that were largely dictated by the color of their skin.

As the workshop neared its end, it focused on the Christian response to racism.

“We are talking about how much racism alienates us from one another,” said Janice McWhertor, another of the facilitators.

“Often the result of racism is a loss of humanity. It dehumanizes us and does nothing to honor God.”

The way forward, she said, is to trust in God and to embrace his teachings about the beauty and the quality of all believers who will one day appear before his throne.

Carpenter said white people attending the workshop may not be the kind of powerbrokers who set the agenda for how society operates. But that does not let us off the hook.

We must continue to work to become aware of our own racism and the degree to which we can address it in order to help dismantle a system built upon privilege.

"This is the area in which most white people can provide leadership. They can serve as gatekeepers in whatever institutions of which they are part," said Carpenter.

By being aware of racism and its impact, we may be able in some small ways to deal with this far-reaching sin of the soul in the small world in which we live and in the broader world.

"Our central task as Christians is to realize the destructive power of racism," said Kafi Carrasco, a facilitator.

"Our work for the rest of our lives is to continue asking God to realign our identities. This doesn't mean that we can overcome racism right away, but we can be in this space of moving toward transformation."