Winter Creatures Teach Us about Waiting for the Light

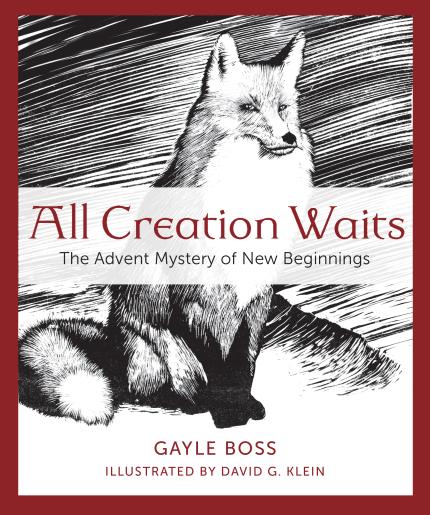

A fox is featured on the cover of the new book All Creation Waits.

Several years ago, freelance writer Gayle Boss created a special Advent calendar for her children.

She put the calendar together as a way to show them the joy and powerful sense of expectancy that this season leading up to Christmas can offer.

The calendar sat on a table in their home. It had a door for each day of Advent, and behind the doors were images of such things as the sun, the moon, a small church, an animal, and people.

“I wanted to give my kids a sense of what this season was really about. I made it vivid for them,” said Boss. “We would open a door each day and talk about what was there, and they loved it.”

The calendar she made several years ago became the inspiration for her new book, All Creation Waits, which features a different animal for each day of Advent and offers poetic reflections on how each of the animals adapts when the darkness and cold of winter set in.

“The animals show us in twenty-four different ways the deep mystery and abiding truth at the heart of the Christ story,” said Boss.

Accompanying her reflections are woodcuts of each animal by artist David G. Klein, ranging from a fox, as featured on the cover, to a muskrat, a chickadee, a turtle, and a deer. Other animals include a frog, a raccoon, a chipmunk, a loon, a black bear, an opossum, a bat, and a turkey.

Boss read from her new book to a group gathered recently at the Calvin College nature preserve. Before she spoke, she reflected on how little she knew about Advent when she grew up. Her Protestant church didn’t celebrate this liturgical season.

Some years later, while attending a church in Washington, D.C., said Boss, she had something of an awakening.

As fall ended and winter began, Boss said, she had often found herself dipping into depression. The time of year was growing dark, and so too was her mood.

As she was doing research for her church in Washington, she learned some of the history behind Advent. She discovered how in the fourth century Christian church leaders started to celebrate what we know today as Advent.

“Back then, as the people saw light decline, they believed their crops and food supply were in danger, and they feared the light would never come back,” said Boss, who attends Monroe Community Church in Grand Rapids, Mich.

To counter their fears, church leaders began to emphasize a time of hopeful waiting as the light of the world, the birth of Christ, approached, she said. During this time, they called for the people to pray, to fast, and to give alms to the needy.

In many ways, church leaders acknowledged the fear of darkness but emphasized worshipful ways in which people could act as they waited for light to return again.

“When I learned about this, I suddenly felt more sane,” said Boss. “I saw how it is natural that there is this time of stripping down and of how you wait in the dark for Christ to return, and then you celebrate.”

She carried her own practices and appreciation of Advent into her home when she became a mother—hence the homemade calendar. And now there is the book.

“Advent is about darkness and hope and fear and loss and hope,” she said. “In my book I want to convey the ancient truths that the church fathers wanted to teach.”

In All Creation Waits, Boss does this by focusing on how various animals grow quiet and often turn in on themselves to gather and sustain their resources when the trees lose their leaves and the wind blows cold and the ground hardens with frost.

She writes about their habitats and their characteristics.

“For example, the book has a beautiful woodcut of a turtle, and I write about how it burrows in the mud and waits, of how it prepares itself to hibernate,” she said.

She also writes about muskrats—furry animals that know where to find food when snow and ice cover the ground.

Of the chickadee, she writes:

“Half-an-ounce of feather, flesh, and hollow bone, a chickadee in your palm would feel like the weight of two nickels. Like any living thing light-weight relative to its length and width, it loses heat quickly. So the little bird must eat continually during winter’s short daylight hours to stoke its metabolic fires for the long night to come.”

Overall, she said, she hopes her book appeals to a range of people “who know there is a larger truth at the heart of the universe—that there are other ways to get at truth, to see through these animals, and how they live, that the dark is not the end.”