Speaker Talks of Cultivating Character

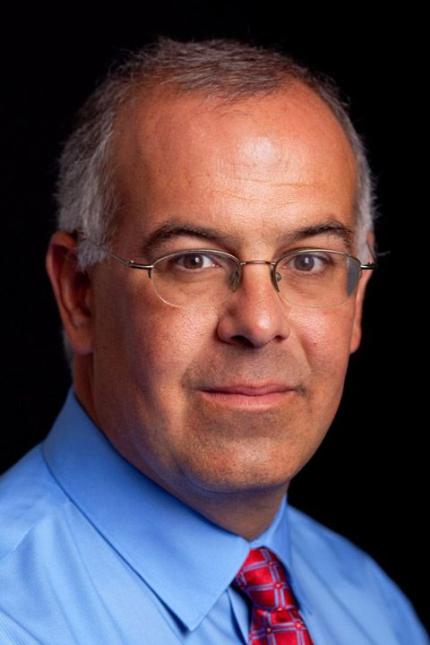

David Brooks

David Brooks is an Op-Ed columnist for the New York Times — a job that may look good on a resume but hasn’t necessarily made him a good person, Brooks said at the January Series 2016.

In a talk sponsored by Calvin Seminary’s Center for Excellence in Preaching, Brooks said he often thinks he was born with a “natural disposition toward shallowness.”

That happens especially, he said, when he meets people such as the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan Buddhist leader.

“The Dalai Lama radiates an inner joy. I sat next to him one time, and he just started laughing.You had to laugh with him,” said Brooks, who is also a commentator on NPR and the PBS NewsHour.

“When I meet people like that who radiate an inner light, I realize I don’t have that inner light and want to try to figure out how to get it.”

One way he sought to do this was by coming out with a book, The Road to Character, in the introduction of which he said he wrote the book in hopes of saving his soul. But so far, he commented at the January Series, that hasn’t really happened.

Still, writing the book gave him a chance, by examining the lives of others, to discuss ways needed for building one’s character — for growing in maturity and faith in things higher than oneself -- and learning that this begins only with a painful process of self honesty.

“You often need to forget yourself to find yourself. It is a paradox,” he said. “Each of us has a core sin (things like greed, lust, or pride), and character is built by confronting our sin.”

In his book, Brooks profiles people who confronted themselves and in so doing found a new commitment that helped them to live a more virtuous life.

For example, he writes about the fifth-century theologian Augustine, former U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, and social activist Dorothy Day.

Augustine turned his back on a lifestyle of loose living and devoted himself to God. Eisenhower needed to confront and master his temper in order to become a great general.

And Day, he said, became a strong advocate for the poor after she left bad habits behind and was overcome by transcendent joy following the birth of her child.

These are people, said Brooks, who faced their own demons and sinfulness, became aware of themselves and their shortcomings, and grew in character and humility.

These people, along with others he writes about in the book, such as the 17th-century essayist Samuel Johnson, had a “radical self-awareness and honesty. They were willing to confront their own brokenness.”

Too often in today’s society, Brooks said, people shy away from doing this — from seeking to cultivate what he calls the “eulogy virtues.”

“These are the things people say about you when you die. They include such qualities as humility, kindness, and a willingness to face your own weaknesses,” he said.

Instead, people tend to place a great deal of emphasis on the “resume virtues” — obtaining high test scores in school, achieving success in a career, accumulating wealth, having a nice home.

Brooks doesn’t suggest that people must ignore the resume virtues, since you need them to help pay for the things of everyday living as well as to give you a sense of worldly accomplishment.

But he does suggest that people will do well to seek and cultivate, for their own betterment and for the world itself, the eulogy virtues.

“The question we need to ask is ‘What is life asking of me?’ not ‘What am I asking of life?’” he said. “We need to commit to something outside of ourselves.”

Perhaps the best example of lasting commitment, he said, is reflected in a marriage that endures, in which spouses remain at each other’s side long after the initial passion subsides.

“Likely the decision of whom you will marry is the most important decision you’ll ever make,” he said.

Marriage is the type of commitment that, Brooks said, requires setting aside one’s ambitions for the good of the other. “There is a vulnerability and durability in this love,” he said.

While this kind of love — whether in a marriage or in other areas of life — is often hard to achieve, it can offer great rewards.

“Love humbles you,” he said. “You realize you are not in control of your own mind. Love also plows open the hard ground. It reminds you that the riches are not in yourself but in others.”

During a time for questions after his talk, Brooks offered opinions on such topics as Tuesday’s State of the Union address by President Obama.

He said he felt sad as he listened to Obama’s State of the Union speech, in part because of how the president discussed his inability to bring opposing political sides together to pass laws that would better address the nation’s problems.

“He is a man of high intelligence and integrity. I admire him personally and yet may disagree with him politically.”

Brooks noted that in his speech the president listed many intractable problems, such as the terrorist threat of ISIS, the need for gun reform, and the ongoing challenges posed by a slow economy. “Maybe,” said Brooks, “if the system was better, he could have solved some of them.”

When asked who was the person in his book that he admired most, Brooks said it was Augustine.

“He is probably the greatest mind I’ve ever encountered,” said Brooks. “He was an ambitious young man with great abilities who was restless until he met God.”

Brooks then read for the audience Augustine’s poem “What Do I Love When I Love My God,” part of which says. “I do love a certain light, a certain voice, a certain odor, a certain food, a certain embrace when I love my God. . . .”

Augustine was someone who had a “ferocious commitment to something beyond himself” and who “worked hard throughout his life to be a better person,” Brooks said.