Festival of Faith and Writing Explores the Power of Sacred Words

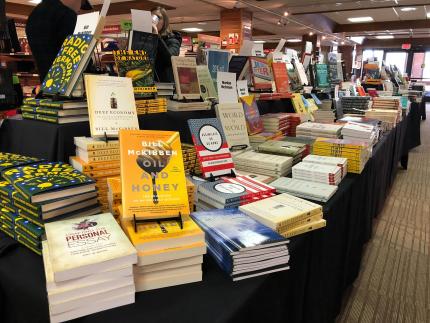

Books by Festival of Faith and Writing authors

Calvin Festival of Faith and Writing

“In the beginning was the Word,” says the disciple John at the start of his gospel account. Keeping that in mind, the sacred words we use to express the mystery, meaning, and power of the Word are significant.

This theme ran through a number of speeches and presentations at Calvin College’s 2018 Festival of Faith and Writing, Apr. 12-14.

Attended by over a thousand people, the festival addressed topics from writing about politics to the writer’s life, including how writing itself can be prayer, how writing can bring you closer to God, the spirituality of making lists and how choosing the right words in poetry and prose can express how God is the source of our comfort and joy.

During her talk, titled “Reading, Writing, and the Art of Preaching,” Fleming Rutledge, an Anglican priest and author, explained the importance of using the right words — words with substance and power — by sketching a history of good sermons and discussing what makes a sermon more than just a personal reflection.

As she started her presentation, she described how reading the book Early Christian Rhetoric: The Language of the Gospel by Amos Wilder taught her the value of words as they were used by early Christians and how they should be used today.

“Amos Wilder talks of how God’s Word is a word that has depth of power. He speaks of how the gospel and preaching this Word of God opens up dimensions in people’s awareness,” said Rutledge, author of the prize-winning The Crucifixion: Understanding the Life of Jesus Christ.

Wilder’s book taught her, she added, that in order to speak true words about God, the preacher must be aware of the profound mystery being addressed in a sermon. A preacher must speak about that mystery from experience.

And then, combining words inspired by the Bible and other sources of good writing, be it poetry, fiction, or nonfiction, the preacher must proclaim, not just explain or exhort, the Word to the people, said Rutledge.

“Ultimate matters are at stake here,” she said. “Something goes on in good preaching that is not about me but comes from another place of power altogether that cannot be forced, but comes from the grace of God,” she said.

“Good preaching is about the gospel, which has an invasive quality that opens up space in people so God can invade that space.”

Words do matter when we speak of the things of God, said Jonathan Merritt, another festival speaker, but he fears use of those words dying and we need to do something about it.

In his presentation, “The Death and Resurrection of Sacred Speech,” Merritt described what he encountered after moving to New York City from Georgia a few years ago. He said he saw a landscape filled with churches, mosques, temples, and other places of worship. Manhattan alone has nearly 1,800 of these sites.

But as a writer and blogger on topics of faith, Merritt was quickly startled to find that, despite the trappings, New York City seemed to be “an iron wilderness” where he rarely heard people talk about subjects such as God, grace, or salvation.

“Upon moving to New York, I ran into a crippling language barrier. I no longer heard” people talk of spirituality or things that are sacred, said Merritt, author of a book coming out in August titled Learning to Speak God from Scratch: Why Sacred Words Are Vanishing — and How We Can Revive Them.

In researching the book, he found studies and articles detailing the death of sacred language over the past 50 years or so. Partnering with a research firm, he learned that as many as two-thirds of Americans rarely, if ever, speak about God, and only about 13 percent have a spiritual conversation every week.

“People are put off by spiritual language today — perhaps because they have been hurt by sacred words,” said Merritt. “Perhaps religious language is no longer relevant to everyday life.”

Reasons for this may well be that the language Christians have used seems empty and meaningless in a digital age filled with a dizzying array of communications possibilities, spiritual options that seem more pleasing and a growing number of people leaving traditional churches.

But the situation can be turned around, said Merritt, by committed Christians seeking and then expressing a richer and fuller language of the faith.

“We must struggle to articulate what we believe and love. Maybe we need to learn to see God from scratch,” said Merritt.

“There are creative, imaginative ways to speak about God. We need to wake up to the reality that the language we used when churches were full and [life seemed more] secure no longer works so well.”

In the panel discussion called “How to Write — and Live — When the World Is Burning,” Kyle David Bennett said that writing for him is “fighting against selfishness and greed. These things have to be named and spoken of.”

Following Jesus means “speaking words of truth and layering them with beauty and truth even if the world is burning,” said Bennett, an assistant professor of philosophy at Caldwell University in New Jersey and author of Practices of Love: Spiritual Disciplines for the Life of the World.

Writing as a follower of Christ, especially in today’s world of wars and mass immigration, means being a witness to the gospel and often doing it by describing “how you are living the way of Jesus in your life right now,” said Sarah Arthur, who wrote The Year of Small Things: Radical Faith for the Rest of Us with Erin Wasinger, another of the panelists. The book tells the story of a year in the life of their families.

At another panel, titled “Whose Story Is It Anyway? When Ministers Write Memoirs,” Ruth Everhart, a Presbyterian pastor, said choosing and using the right words was very difficult when she wrote the story of being robbed at gunpoint and raped, along with two other young women, when she was a student at Calvin College in 1978.

On the one hand, she said, she didn’t want her words to hurt people connected to this story, but on the other hand she wanted to make sure her book, Ruined, expressed the many struggles she faced as the result of the crime.

“I felt shame over what happened and, in writing this, it was such a delicate subject,” she said. “Even though people don’t want to tell their most terrible stories, it helped me on the next step of recovery and redemption.”

Carol Howard Merritt, also a Presbyterian pastor, said that recalling and chronicling her story of growing up in an abusive home was painful but also beneficial.

“Writing about it was an incredibly powerful act to do and go through,” said Merritt, author of Healing Wounds: Reconnecting with a Living God after Experiencing a Hurtful Church.

Her book opens with a scene in which she listens from her bedroom while her father, a minister who used Bible verses to justify his violence, and her mother are once again throwing things and yelling at one another.

But in that chapter she also describes standing by her bed and receiving an experience of God that was crucial for her in dealing with the trauma in her home and the harsh treatment in the church that she experienced in the years ahead.

“It was hard trying to figure out what form the book would take but, instead of focusing on the pain, I focused on the healing,” said the Presbyterian minister. “I was brought to a difficult place, but it allowed me to heal in the context of my writing.”

Already, things are moving ahead to put together the Festival of Faith and Writing for 2020. Stay tuned