Singing the Genevan Psalms

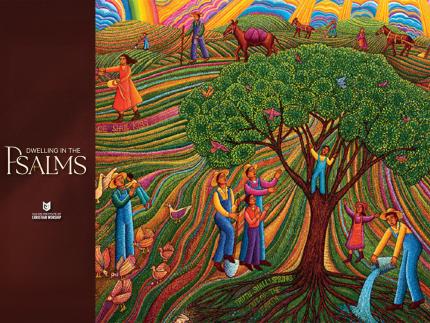

On October 28, in the first event of a yearlong series on Dwelling in the Psalms hosted by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, Dr. Karin Maag described the history of psalm singing in the Reformed tradition, even helping to lead the audience in singing some psalms along the way.

Maag is an expert on Reformation theologian John Calvin and on the Genevan psalms, and she serves as director of the H. Henry Meeter Center for Calvin Studies at Calvin University.

After a brief introduction, Maag joined a small group of singers to lead the audience at the Calvin University Chapel in singing “Our Help Is in the Name of God the Lord,” based on Psalm 124, a psalm of praise and thanksgiving for God’s care and protection. The psalm was sung regularly in Geneva during the Reformation period, Maag explained. One occasion when it was sung was in December 1602, when Geneva had been attacked overnight by the Roman Catholic Duke of Savoy. The Genevans repelled the attack, Maag said, and on the next day, a Sunday, they sang this song in church, giving thanks to God for his deliverance.

Maag next described how in December 1551 the Genevan government jailed their chief psalms composer, Louis Bourgeois. His offence was not related to violence or disruption, but, according to the magistrate’s minutes, had to do with changes Bourgeois had made to some psalm melodies in an attempt to correct past printer errors in the music. Even intervention from John Calvin could not succeed in releasing Bourgeois or allowing the changes to be made to the music. The city council decreed that the psalms could only be sung to the old, familiar melodies. (Thankfully, Bourgeois was released after only one night in jail but was told not to attempt to alter the melodies again.)

While John Calvin is closely associated with the Genevan Psalter, he did not originate the practice of singing biblical psalms set to poetic meter, said Maag. Rather, he learned the practice from congregations in Basel, Switzerland, and in Strasbourg, then a culturally German city with ties to the Holy Roman Empire, where he spent time as an exile and led a congregation of French refugees. He adapted the practice of psalm singing and, in 1539, published a set of 19 psalms, including six he had written himself. The initial versions were not well accepted, and later versions were adjusted to better fit different languages and syllabic stresses.

The complete psalter appeared in 1562, with 125 melodies for 150 texts, plus the Song of Simeon and the Ten Commandments. Printers and publishers worked together to make the book available, creating 30,000 copies in a time when print runs were usually under 1,000 units.

Versifiers of the completed Genevan Psalter included John Calvin, Clément Marot, and Theodore Beza. Music composers and adapters included Guillaume Franc, Louis Bourgeois, and “a certain Master Pierre,” said Maag. Some melodies were based on simplified Gregorian chants and earlier Roman Catholic hymns.

Maag stressed that the creation of the Genevan Psalter was not a one-time project but had developed slowly over decades. The aims were explained in the prefaces of various editions provided to congregations. In Calvin’s edition, he noted the powerful impact of music on the human soul, encouraging congregations to view music as a gift from God. Because of this power, he sought to regulate songs so that music would always be used to glorify God. As a part of this goal, he ruled that the words sung needed to be from Scripture and that melodies were to reflect the words’ weight and majesty, Maag explained.

Beza laid out his goals in a poem, seeing psalms as important for persecuted Protestants. The psalms are significant for people suffering and living in fear, pointing to deeper meaning and a focus on spiritual truths.

Bourgeois’s stated goals – in the same preface that had landed him in jail for altering melodies – concentrated on getting congregations to sing well. He complained about poor singing, noting “the dissonance that too often occurs during the singing of the psalms because of those who understand nothing in music and who nevertheless want to be heard above all the others.” He encouraged people who were not skilled in music to listen to others until they could confidently join in.

Maag explained that psalm singing in Reformation Genevan worship was done unaccompanied and in unison. Organs existed from the Roman Catholic days of many churches, but those instruments often sat unused during the early Reformation. Calvin acknowledged the call even within the psalms to use instruments in worship but interpreted that use as part of the old covenant “of shadows and figures” and no longer useful for public worship, based on Paul’s exhortation to pray and praise only in a known tongue (1 Cor. 14:13).

Another feature of psalm singing was that it was very organized, said Maag. A chart helped people know which psalms would be sung in which service. The psalms were selected in advance, and every church in Geneva sang the same selection each Sunday. Singing the entire collection of psalms would take place over the course of 25 weeks, covering each psalm twice in a calendar year, with the Ten Commandments and the Song of Simeon sung quarterly.

Singing at home could be done in harmony rather than in unison, and separate psalters were created for home use to facilitate this. Instruments were also allowed for private worship in the home.

To help congregations learn the psalms, a teacher would teach children to sing and would also serve as a lead singer for worship services, where adults were still learning. Geneva’s school curriculum included an hour of singing each day, training students to be able to help lead in church and to be more confident in singing the psalms as they grew. To keep things simple, the melody was in the tenor line, which was the only line sung in public worship. Versions for private family worship added harmony for bass, alto, and soprano voices.

Maag noted that while some pastors and song leaders struggled to get their congregations to sing well, others found it difficult to get their congregations to sing at all. Since the psalms took practice to sing well, church leaders in areas with fewer trained musicians – such as rural areas – sometimes sought help from other congregations to help their own congregations learn the songs.

Marot’s French psalms were popular even in Roman Catholic France, said Maag. Dutch psalters using Genevan melodies made their way to the Netherlands. Peter Datheen and Philip Marnix each created Dutch psalters, though synods in 1568 and 1578, presided over by Datheen, instructed congregations to use the Datheen Psalter. Though Marnix’s psalter (1580) was more faithful to the original Hebrew text and better fitted to the melodies, said Maag, most churches had already bought copies of the Datheen Psalter, and it was not practical to replace them.

In the early 1600s, church leaders noted that psalm singing was not going well; singing was slow and plodding, making it difficult to sing entire psalms and to understand what the words meant. The goal of singing the psalms to foster understanding was being undermined. One church leader suggested that organists play the psalms more quickly as preludes, and that cantors and school children should lead and learn to sing the psalms more quickly.

Similar problems arose in Scotland as churches there adopted the psalms. Wars and social turmoil led to difficulties in obtaining and learning music, so a psalm book of only 12 simple melodies was widely used. The tunes were simple and could be sung more quickly, but the use of fewer melodies for 150 psalms sometimes created confusion about which psalm was being sung during a service.

Genevan psalms used minor keys for psalms of lament or repentance and major keys for psalms of joy or thanksgiving. This practice went out of use as some churches moved to common-meter tunes.

In Hungary, a high-quality psalter set to Genevan tunes was created, but some leaders wanted to use Hungarian tunes, and two camps arose.

As Europeans moved to North America, differences between nations and churches moved with them. The first psalter to be written and printed in the English colonies in North America was The Bay Psalm Book, printed in Cambridge, Mass., in 1640. The melodies used were mostly common-meter tunes rather than Genevan tunes.

Choosing which tunes to use in churches became a way of declaring which Reformation focus was used at a particular church. Congregations singing Genevan tunes showed that they embraced the Genevan model of Reformation thought, while congregations singing common-meter tunes declared a measure of independence.

During a question-and-answer period after Maag’s main lecture, a former missionary noted the spread of the Genevan psalms, describing the singing of French Genevan psalms in worship in churches in Mali.

In response to a question about when unison singing ended, Maag explained that when Reformation churches started using organ music again, after allowing it only for preludes and postludes for many years, they soon realized that instruments could encourage congregations to sing faster, solving the problem of plodding singing. As churches incorporated instruments, part-singing came into use again in worship services as well.

The transition from singing only psalms to including both psalms and hymns in worship is a whole different matter, said Maag. Still today in some Reformed congregations, hymns can be sung at home or before a worship service, but only psalms may be sung during the service.

Maag and the group of singers closed the presentation with a rendition of “All People That on Earth Do Dwell.”