Learning the Cost of Generational Trauma

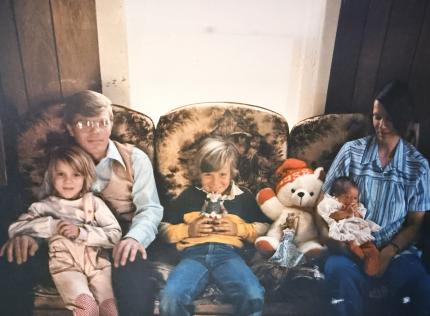

My story began as a little girl growing up in poverty, shaped by life with a severely abusive, alcoholic father. I learned early on that after he drove drunk and hit a tree, he suffered extensive brain damage, which would require relearning how to speak, eat, and walk. While he was hospitalized, my mother left Arkansas for Missouri, likely for the tenth time, but this time for good. Because of the severity of his injuries, she was able to stay and begin building a life as a single mother to three children.

An opportunity to flee domestic violence led us to a small town in Missouri. There, generational trauma continued to leave very basic needs, such as food and heat during the winter, unmet. The seven- and nine-year age gap between my older siblings and me left me home alone for much of my childhood. By the time I was eight or nine, my brother and sister were long gone, finding the reprieve they needed from the reality of our childhood.

My mom did not get everything right, nor did she do it all wrong. Later, I learned the phrase, “She did the best she could with what she had”—a phrase I still struggle to find comfort in.

At the time, I did not have language for what I was living through. I only knew what it felt like…

- Living in a single-wide trailer with holes in the flooring where I could see straight through to the ground beneath.

- Watching my mom decide which food items to put back after her payment was declined at the store.

- Seeing a single pink can of salmon in our pantry, received in our Angel Tree grocery bags.

- Fearing every car ride, knowing how many times we had been stranded on the highway, or worse, riding in a stranger’s car after ours had broken down.

- Being alone on Christmas too many times.

- Knowing my December birthday made an already tight month even tighter.

These are more than hard memories; they are the hidden costs of generational trauma. They are the lasting effects of poverty, addiction, and violence passed down—not because people want it, but because no one interrupts it soon enough.

It was not until my husband and I went through our interviews and home study to become foster parents that I began to understand how deeply that trauma shaped my childhood. As I learned how early neglect and instability affect the developing brain, I realized I was reading my own story on paper.

What I once assumed was normal, I now understand as costly. Costly to my sense of safety. Costly to my understanding of worth. Costly in ways that followed me into adulthood. For many years, it showed up as food insecurity, a need to fix everything, and impatience with my husband and daughters.

Despite all this, neighbors made sure I was fed and took me to their small church located on the outskirts of town. That matters now more than I realized then. I can’t count the lonely, cold days I had at home, but I can say someone noticed and quietly showed a little girl she mattered.

Becoming a foster parent made me confront these realities. Learning about childhood trauma for my foster children also let me give a voice to the girl who learned to disappear, endure loneliness, and need less.

Justice, I have learned, often looks less like systems and more like presence. It looks like a neighbor who notices. An adult who intervenes. Someone willing to stand in the gap long enough to interrupt what would otherwise be passed down.

I share these things not to receive sympathy, but because I believe God has shaped me to have a voice for children from hard places. Learning the cost of generational trauma has changed how I advocate for others. I am determined to help people understand that having even one adult step in and tell a child, through words or actions, that they are worthy can be enough to imagine a life beyond survival.