Learning about AI from the Bible

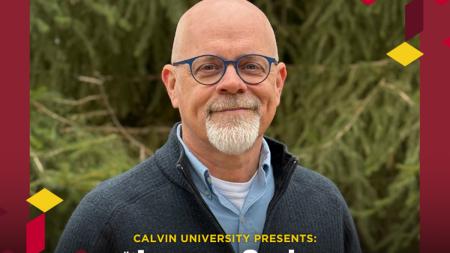

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a tool that promises incredible technological advances, said Christopher Watkin, an author and university scholar in the annual Stob Lecture at Calvin Theological Seminary.

At the same time, because this technology is still in its infancy, Christians need to be part of the public debate over how it should be used, Watkin added in his lecture on Tuesday, Nov. 18.

In fact, now is the time for that debate because we are in a “horseless carriage moment” of AI development, he argued, likening the current state of AI to the time when society was trying to understand – and was conscientiously discussing – the newly invented automobile.

The Stob Lectures are sponsored annually by Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary in honor of Dr. Henry J. Stob, who taught at both institutions. The subject matter of the lecture series is related to the fields of ethics, apologetics, and philosophical theology.

Watkin, who teaches at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, began his presentation by encouraging the audience to think not only of what AI can do for them, but how it is forming them and what it reveals to us about ourselves. Essentially, he offered an overview for Christians to use in trying to sort through the many issues AI and its large language models pose.

“There are those who say AI will do all of the economically valuable work in a decade or so,” said Watkin. “This brings up many questions, such as ‘What is the point of human work if these large language models are achieving all of the work for us?’”

Considering the matter of work, Watkin asked his listeners to consider how the jobs we have define us. He also asked how our work is related to the things God wants for his people.

“These are questions that are dear to Christians, and the Bible has very rich responses to these questions in ways that have not necessarily been asked in recent times,” continued Watkin, who studies the relationship between philosophy and theology.

As he strolled back and forth in the front of the seminary auditorium, Watkin used the Bible as the framework to make his points. He began with Creation, moved to the Fall, and continued on to Redemption to explain ways in which Scripture can be used by Christians looking at, he said, “who we are in relation to AI.”

Beginning with Creation, he explained, we need to realize that, although work is important to us, we should not define ourselves by the work we do. This is important, stressed Watkin, because generative AI will likely do most of our work better than we can in the future, and if we build our worth on our productivity, then AI will threaten our self-worth.

“As Christians, we need to know that AI is not some kind of deity,” said Watkin. “We as humans are significantly different from large language models.”

Still focusing on Creation, he noted that God commissions us to be active and involved in the world, and this includes the work we do.

But, as the book of Genesis makes clear, Watkin said, God created us to have communion with him – that is, we are created in God’s image, and it is in that image, and not work, that we find our identity.

“We must realize that work is only one way to express who we are before God,” said Watkin, author of Biblical Critical Theory, which was named Christianity Today’s 2024 Book of the Year.

Watkin went on to ask his audience to think about the idea of “friction,” the labor required to complete a task.

With this in mind, he said, we need to distinguish between friction, on the one hand, and the pain and frustration that friction, on the other hand, can cause as we work.

At the same time, he went on, we should recognize that not all friction is bad because it has to do with how we develop as human beings. Pain and frustration may be the result of friction, but they are not the same thing.

So, he noted, if AI has the capacity to reduce the friction of work down to virtually zero, we need to begin asking, “How much friction does a person need?” Perhaps, he suggested, if we don’t need to work, we’ll decide, to our detriment, that we need no friction at all in our lives.

Turning to the Fall, Watkin moved into the area of morality, talking about sin and how we as humans are affected by it and what God asks us to do about it.

“What is distinctive about humanity?” he asked. “It is that God holds us accountable for how we treat him and his work. We answer for what we do, and there are consequences. For instance, we are asked to repent, to seek forgiveness.”

Keeping this core reality in mind, said Watkin, it’s critical to realize that no large language model can be held accountable in the same way as humans who, he went on, “are the ones left to live in the face of judgment.”

AI is treated very differently, he continued. “If it makes mistakes, it can be reset and retrained” in ways that human beings cannot.

Also worth thinking about in relation to how we differ from AI is that we are finite. We will die, said Watkin, and “because we are finite, our choices mean something and matter. There are stakes to the choices we make as humans.” AI, left to itself, is a machine, lacking a conscience as well as introspection.

Finally, Watkin spoke about Redemption and focused on the opening verses in the gospel of John, which explain that “the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.”

“We are speaking of the incarnation in which something extraordinary happens,” said Watkin. “God becomes mutually related to us. In Jesus, he comes to share our condition, and that is a million miles away from the large language models.”

Continuing to focus on forgiveness and repentance, Watkin added, “While AI can output words of forgiveness and repentance, it doesn’t really understand what it means to wrong someone.”

In contrast, he maintained, “When we forgive someone, it has to change a relationship in some way. To say ‘I forgive you’ is not the same thing as forgiveness.” Words matter, but emotions and how we actually live out and show forgiveness are key, said Watkin.

Similarly, AI might say the word “love,” but it has no way of knowing what that means. Nor does it speak in the first person, expressing a heartfelt emotion. Instead, it distills what millions of humans have said in similar situations in the past.

“Large language models are indifferent to others. AI doesn’t speak in reference to what is true, it simply produces likely language and cannot be sincere,” said Watkin.

In the end, especially as Christians, said Watkin, we have the opportunity to reflect on how our relationship to God offers us dignity and hope.

Essentially, the Stob lecturer made clear that he believes we are members of God’s family and, with the Lord’s guidance, have the capacity to act and live with honesty, clarity, and connection to others.

In relation to AI, Watkin said, we ought to consider how it remains a technology that can only mimic words that a world of websites can feed it.

As he concluded his lecture, he said, “Seize the day; beware of the dangers.”