Black Theology Offers Hope

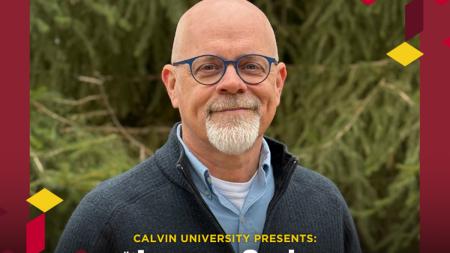

Embedded in the practice and purpose of Black theology are biblical truths and a range of experiences, many traumatic, that can speak to and even help to transform the Christian church today, said Dr. Esau McCaulley at the January Series on Wed., Jan. 25.

“I believe that the church at large can learn from how Black people have [down through the years] interpreted the Bible,” said McCaulley, an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College. He is also an Anglican priest.

“The Black ecclesial tradition has something to say that strikes a different note than the standard options often given to students of the Bible and theology,” writes McCaulley at the end of the first chapter of his prize-winning book, Reading While Black.

McCaulley, a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, gave this year’s Stob lecture at the January Series and spoke in a question-and-answer session later that day at the Stob Lectureship Colloquium at Calvin Theological Seminary. The Stob lectures are sponsored annually by Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary in honor of Dr. Henry J. Stob, who taught philosophical and moral theology for many years at the seminary. The subject matter of the lectureship is related to the fields of ethics, apologetics, and philosophical theology.

In his January Series presentation, McCaulley sketched the history of how Black people responded to the circumstances in which they found themselves in the slaveholding American South.

Initially, he said, white evangelists came to the South to bring the gospel message to Blacks. But because this message focused only on one part of a Black person – saving his or her soul, not their entire selves – Black people eventually began their own churches, which offered a more full-bodied view of Christianity and their place in it, said McCaulley.

“They found out that they couldn’t be Christians in the spaces they were in. So, in order to worship God faithfully, they created their own spaces. They found the freedom to form their own religion, to be who they are and who they wanted to be,” said McCaulley.

For the most part, the theology and the churches they developed arose from the struggle for freedom from slavery. In addition,

said McCaulley, they considered the biblical narrative as that of God’s people rising out of oppression and following the leading of the Lord to a new life and a new place in the world characterized by a focus on a faith deeply involved in the society and culture in which it found itself.

Many of these churches developed out of the Baptist and Methodist traditions, given that these traditions offered fewer obstacles to people seeking to form a faith community.

“This theology is only one [but a powerful] strand of Black Christians opposing slavery,” added McCaulley. “There was a strong emphasis on brotherhood, on one blood, and how, because we are all part of the human family, we should be together.”

Other strands of this theology, he said, developed churches that emphasized accommodation with the larger white society, and there were “holiness churches” that had a strong focus on the Holy Spirit. In addition, there was a movement away from forming churches and seeking separation from mainstream Christianity.

“There are important elements to all of these strands, and we need to recover and express them all,” said McCaulley. “We need in the public square to find a way to include all of these Black voices and their critique of [mostly white] Christianity.”

Most Black churches, as they have grown over time, have a strong connection to biblical orthodoxy and to addressing issues of social justice, he added.

In essence, said McCaulley, this is a theology that is “socially located in that it clearly arises out of a particular context of Black American experience. Also, it is willing to listen to the ways in which the Scriptures themselves respond to and redirect Black issues and concerns.”

With its focus on a careful, sympathetic, and patient reading of the Bible, he added, there is a blessing and value that extends far beyond Black churches.

“This is a transformational, ecclesial tradition . . . that is willing to listen to and enter into dialogue with Black and white critiques of the Bible in hopes of a better reading of the text,” he said.

McCaulley said he believes the best elements of the Black church tradition – “its public advocacy for justice, its affirmation of the worth of Black bodies and souls, its vision of a multiethnic community of faith” – offer a path that embodies hope – a hope grounded in the biblical narrative and a sure hope sorely missing in much of the church today.

Theologians who have helped to develop a Black theology of liberation with a strong push for social change and equality have included David Walker (1785–1830), Frederick Douglass (1817–1895), Howard Thurman (1900–1981), and James Cone (1938–2018 ).

And that theology, alive and vibrant in Black churches, said McCaulley, came to be a rich and valuable expression in the civil-rights struggle, pushed by such leaders as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“We look at the entire Bible and see how God reveals himself across the narrative,” said McCaulley. “Black theology interprets the Bible uniquely. It believes that theology arises out of a particular context.”

Looking at where the Christian church is today, McCaulley said, there is a clash of narratives in how to read and interpret Scripture. And as a result, in this mix of views Black theology can be considered “a gift of the moment.”

“We have learned to do theology without power,” meaning this theology came from a particular setting in which people grew in faith although they were not in positions of power – and this bred humility in the face of the all-powerful God, he said.

In addition, Black churches have largely “learned how to deal with the disappointments with other Christians,” McCaulley said.

Black theology, with its strength and helpful vision coming from a willingness to preach a gospel for all broken, oppressed, and needy people, offers a clear-sighted approach that the broader church could find useful, said McCaulley.

“We can offer what we have to the wider world,” said McCaulley. “We believe the Black presence is a manifestation of God’s color-blindness and love and acceptance for all people.”