Polishing the Chain

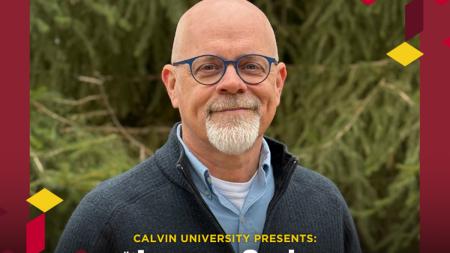

“The idea that we can have good relationships with each other is what this weekend is all about,” said Adrian Jacobs at the opening reception of the May 25-28, 2023, Canadian National Gathering, where 150 people had gathered to focus on the work of reconciliation with Indigenous brothers and sisters, and to discern next steps for the CRCNA in Canada.

Jacobs is part of the Turtle clan, Cayuga Nation of the Six Nations Haudenosaunee Confederacy at Grand River Territory, Ont. He is also the senior leader for Indigenous justice and reconciliation within the CRCNA in Canada.

“People sometimes want to jump right to reconciliation,” he said about his title, “but there is a stop before you get there, and it is called justice. It is not something that can be skipped.”

Jacobs provided attendees with a bit of the history behind Indigenous relationships with settler communities in the land we know as Canada. He specifically focused on the covenant made between Dutch settlers and his people, Haudenosaunee/Mohawk First Nation, in 1613.

At that time, the Dutch East India company wanted resources to take back to Europe for a profit. When they encountered Indigenous people, they suggested establishing a trading relationship. Because of language and cultural barriers, it took awhile for the Indigenous populations to understand what was being offered, but eventually they agreed to be in a relationship.

“The Europeans kept looking for kings. They wanted to make a deal with the top guy,” said Jacobs. “But we [Indigenous people] talked about it, and we said, ‘We already know how to make arrangements, covenants, and treaties among our people. We know how to do this.’ We came up with the two-row wampum belt.”

Wampum belts were used by Indigenous people to mark important events and treaties. The belts were made out of beads fashioned from quahog shells, with designs intended to be used as symbols.

“We put into the symbols our understanding of what things were all about,” said Jacobs. “These are our records – our sacred knowledge encoded. And then the stories are remembered by wampum keepers.”

The belt made to represent the confluence of the Mohawk and the Dutch in 1613 is known as the Two Row Wampum. It depicted two purple rows running in parallel together. One row represented the Dutch traveling along the river of life in their ships, the second row represented the Mohawk traveling along the same river in their canoes.

“The river goes off into the future,” said Jacobs about the belt’s design. “It was intended to be a living thing, an ongoing relationship.”

Also on the belt, separating the two purple rows, were three rows of white beads. These represented the relationship between the two groups of people. The first white row depicted a desire for peace; the second, a desire for friendship; and the third, the good mind that makes strong relationships.

“You can’t have peace if you don’t have respect. When you are fully respected, you can relax. You don’t have to guard your heart. You don’t have to judge everyone and keep them at bay. You can be yourself,” said Jacobs.

But after the wampum belt was created, the Indigenous people noticed that the Dutch tended to forget about the covenant and the promises they had made. The Haudenosaunee created a new belt, a covenant belt, to renew the relationship and remind each other of their promises.

For this belt, they used silver chains to show how, if either party ever needed assistance, they could span the distance between them and offer help. While iron links would rust and break, silver can be polished and renewed. This became known as the Silver Covenant Chain, and Jacobs said it was intended to be polished on a regular basis as a way of symbolically renewing the covenant between both parties.

But, still, the Europeans did not keep their side of the covenant.

Jacobs said that he regularly hears people say that since it has been 400 years since the original covenant was agreed upon, it is no longer relevant. This isn’t biblical, he said. He pointed to the Old Testament story where Saul and the Israelites were punished for breaking their covenant with the Gibeonites after 400 years.

“I am telling you right now that some of the suffering that is happening right now in this place and in this world is because of broken covenants,” said Jacobs.

Returning to the purpose of the weekend, Jacobs said that he sees Jesus and the gospel message in the Two Row Wampum. It is all about reconciliation and living in right relationship with each other, which is what Jesus also calls us to, he said.

“Maybe the gospel came to you [Europeans] when you came to us [Indigenous], and you just didn’t hear it. Maybe you were so blind in your cultural ways,” he said.

Jacobs compared this to the story of Abram and Melchizedek (Gen. 14:18-20). Even though Melchizedek was a Canaanite, who spoke in the Canaanite language and had a Canaanite name for God, Abram was able to recognize that they worshiped the same God. Europeans, by contrast, seem to have been unable to do that.

But it is not too late. Jacobs explained that he was at the Canadian National Gathering and had taken on his role as senior leader for Indigenous justice and reconciliation in order to polish the covenant chain once again.

“I am here because my ancestors thought [living in right relationship] was a good idea. I am here to remind you that this is what it was in the beginning, and I am here to be a part of that,” he said.

He added that when the covenant was originally made 410 years ago, the two groups of people were very different. They looked different, smelled different, spoke very different languages, dressed differently, lived in very different ways, and were educated in different systems. Today we all go to the same stores, do the same kinds of things, and even go to the same schools.

“Surely if they could do that four hundred and ten years ago, when we were really different, it should be a piece of cake now,” he said. “I’m here to tell you that we can do it . . . if you are ready. We’ve been ready for four hundred and ten years. When my elders first told us about this, we said this is our best idea. Four hundred and ten years later I don’t know of a better one.”

Not only would this renewal of relationship respect the original promises and covenants that were made, and not only would it be living into the gospel message of reconciling things to right relationships, but it would be of benefit to white, settler, Christians, he said.

“Richard Hill talks about ‘ship-ness’ and ‘canoe-ness,’” said Jacobs. During colonization, the settlers got into the Indigenous peoples’ “canoes,” or ways of being, and forced them out. Their “ship-ness” is now integrated into Indigenous communities. They are thinking like the colonial system, and it has been causing pain, self-hate, and trauma.

“I think my ‘canoe-ness’ is good for you in your ‘ship-ness,’” said Jacobs. “I think we are medicine for you. We are corrective. We are helpful for you. I’ve been doing my best in my own faith walk to get ‘ship-ness’ out of my Christian faith and have more ‘canoe-ness.’ I believe that I, as Turtle Clan, am able to live my Christian faith as who I am as Haudenosaunee. It might sound different from your faith. Maybe it isn’t the sound in your church, but maybe some of that is good for you. It might look different and smell different from what you are used to. But maybe it is helpful to you. I know it works for me. I’m happy with my ‘canoe-ness.’”

Jacobs also pointed attendees to the history of Indigenous work in the Christian Reformed Church. He mentioned how the executive director of the Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada signed a covenant commitment to the Indigenous people in 1987; how Richard Twiss spoke to the World Communion of Reformed churches in Grand Rapids, Mich., in 2010; how there have been decades of work at the CRC’s urban Indigenous ministry centers, how the Canadian Indigenous Ministries Committee has been advocating for Indigenous justice for many years, and how the CRCNA signed on to the commitments of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015.

“I’m not just a new kid on the block with a new message. I am in a long line of people going back to 410 years ago,” he said. “I’m saying the same things my ancestors have said. I’m here to say that things could have been different. Let’s make it that way.”

(Jacobs also spoke about the Two Row Wampum at a storytelling event. Watch the video.)

The Canadian National Gathering was held May 25-28, 2023 on the campus of Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ontario. This is the first in a series of stories about the event. Additional stories will be shared in the coming weeks.