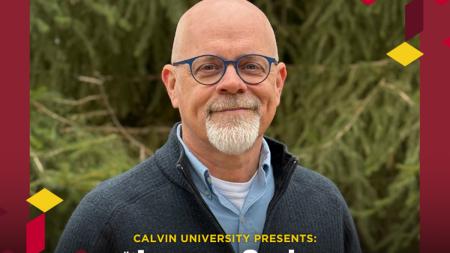

Questions Along the Way: A Life with Autism

In his presentation at Calvin University’s January Series 2024, Daniel Bowman, Jr., talked about his autism diagnosis at age 35 and how he found hope and community in the stories of other neurodivergent writers and artists.

Beginning his talk, Bowman confessed that he was going to go off the script he had been carefully crafting for several months for this presentation. “I’ve been waist deep in the minutia of autistic/neurodivergent storytelling and what that looks like. As I was driving up here, I realized that maybe wasn’t the focus we needed,” he shared. “God seemed to be leading me in a different direction.” He felt led to concentrate instead on answers to questions he is frequently asked.

Examples of some of those questions, he said, are

- How did you get diagnosed?

- What was the process?

- What made you seek diagnosis?

- Why did you write about it?

The diagnostic process is different for everybody, Bowman explained. He was reading, going to counseling, and sensing that some of his questions were finding answers, he said. “I knew I was getting close; I was onto something. Autism doesn’t always come up first. It might be depression, anxiety, bipolar. . . . Autism is hard to pin down,” he said.

Bowman shared that had been living with anxiety and depression for years but didn’t realize they had a deeper cause. Online research led him down a “rabbit hole,” he added, where he eventually found articles about autism.

“When I read about autism, I realized it fit,” Bowman recalled. “It now seemed glaringly obvious. And because it was true, God was in it. It was the beginning of an enormous change in how I thought about myself.”

Seeking to learn more about the diagnosis, Bowman discovered David Finch’s book The Journal of Best Practices. In the book Finch describes how his wife, an autism counselor, decided to confirm her suspicions about him and sat him down with some questions, such as, “Do you tend to get so absorbed in your interests that everything else gets excluded? Before you go somewhere, do you need a picture in your mind so you can prepare? Do you prefer to eat the same food and wear the same clothes every day? Do you get frustrated if your routine gets interrupted? Do you get frustrated if you can’t sit in your favorite seat?”

Finch wrote that he was amazed by the questions and learned that some of the ways he experienced the world were not common to most people. Bowman said he recognized the feeling. Finding a reason and a name for the lifelong feeling that something was different about him was very freeing, he said.

“When you’re different from everybody else, especially in childhood, there’s a lot of shame – you don’t know the reason, so it seems like a failure,” he said. Learning that it’s not a failure but a particular set of characteristics, and that other people live with it and have written about it was an important realization for him, Bowman said.

Being a poet and a professor of English, Bowman said he was drawn to try to sort out this new knowledge by writing about it. He describes his book On the Spectrum as creative nonfiction, detailing his journey after his diagnosis.

Along the way, he said, he began to look for the works and stories of other writers with autism, and he was surprised to find that not many people have written about their experiences with it. “[It’s true that] many autistic people are gifted in areas that are more black and white or require rigid thinking. But it makes sense to me that autistic people are also in the arts. As many as 1 in 36 people are on the spectrum. With that many in the world, many of us will be working in the arts,” said Bowman.

He likes Temple Grandin, a professor at Colorado State University, he said, and respects her work in bringing autism to mainstream attention. In recent years, he explained, the #ownvoices movement encouraged film and other media industries to consult with and hire people with disabilities to represent characters with disabilities. Another tagline, he noted, is “Nothing about us without us.” Bowman said he appreciated how this hashtag helped people find others who could better understand their journey because of a similar lived experience.

At the same time, Bowman noted, he has little in common with Grandin. Though both are autistic professors, he said, the similarities in their interests and experiences ends there. While Grandin’s field is scientific and related to farm animals, Bowman explained, “I teach liberal arts at a Christian college. . . . I know nothing about bovine studies; I’m allergic to many animals. I like early jazz and broadway theater, and the intersection of art and Christian faith. I’ve had moderate success, but I’m pretty average in my field. That’s why I needed to tell my story.”

Bowman went on to explain the danger of a “single story” that comes to represent a large group of people: “These stories are not untrue, but they are incomplete. They limit what the public can understand about autism and autistic experience.”

Julie Brown’s book Writers on the Spectrum has been another formative book for him, Bowman said. Brown explores the lives and works of authors who may have been diagnosed as autistic if they lived today. Stories about them detail awkward social interactions, retreat from sensory overload, and lives of isolation. Their works often reflect loneliness, despair, sadness, dilapidated shacks and upstairs apartments, and images like Alice in Wonderland swimming in a lake of her own tears.

“Ironically this book assuages my own alienation, knowing others have gone through this as well,” said Bowman. “I take refuge in images that have become important to my own thinking [such as] a small boat lost on a vast sea.”

“Autistic writers don’t necessarily write in a straightforward way, but more as a collage,” explained Bowman. His own book, he said, includes a letter, an interview with himself, and interviews with young people living with autism. He hopes it can serve as a memoir that will be helpful both to people with autism and to the people in their lives.

Bowman encourages educators to be advocates for students who learn differently, and to “meet them in the middle” when needed, as time management, deadlines, and task completion can be challenging to some neurodivergent people. Many are brilliant, he noted, but they may need to be reminded that we care and that their challenges are not their fault but the result of a brain that is just wired differently.

“Meeting in the middle” helps in relationships as well, Bowman shared. There are times, he said, when he feels depleted and needs a lot of time alone, but he recognizes that he also needs to support his wife and her needs, helping with housework, errands, and childcare. In navigating these challenges and negotiating solutions, he reminds himself, “It’s not about me; it’s about us.”

When he does need to self-regulate, Bowman said, he takes time alone and finds comfort in the predictability of things like stories, the liturgy at church, and prayer.

Bowman is no stranger to the Calvin University campus. His first time there was in 2008 for the Festival of Faith and Writing. “Suddenly I was in a room with Mary Karr and Katherine Paterson, these luminaries of literature. It changed my life,” he said, adding that he made a connection there that caused him to pursue further education at a Christian university. He returned to attend the festival whenever he could, he said, and he will be a speaker at the 2024 Festival of Faith and Writing this coming spring.