Creating Opportunities

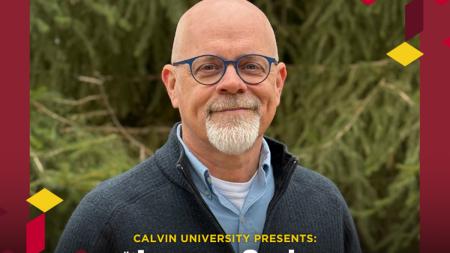

In his Jan. 26 presentation at Calvin University’s January Series, Efosa Ojomodiscussed how innovating in the area of market creation is necessary for sustainability and poverty alleviation.

Originally from Nigeria, Ojomo studied in the United States and became an engineer. He was happy with the way his life was going, he said, but in 2007 he stumbled upon the book The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done about It by Paul Collier, about the poorest one billion people in the world.

“It captivated me like nothing ever had,” said Ojomo. He went on to read two other books referenced in it: The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time by Jeffrey D. Sachs and The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good by William Easterly. As this reading led him to examine his own life, said Ojomo, he realized that he wanted his life’s work to be to help fix the problem of poverty.

He cofounded an organization called Poverty Stops Here. Returning to Nigeria for the first time after leaving there to study in the U.S., Ojomo saw needs among rural areas of the country. He started as many organizations do: by digging wells in several villages where the people had to walk long distances to wash laundry or draw water from rivers. After several months, however, the wells broke down or had mechanical difficulties.

By that time, Ojomo was back in the U.S., and he realized he had no way to maintain the wells. He couldn’t in good conscience continue raising money to build wells that would end up breaking, he said. He decided to find a better way to solve the problem. A system needed to be set in place around the villages and wells to ensure that the people had regular and reliable access and clear ways to maintain the wells. Ojomo changed his focus, realizing that people need to develop solutions that will work in the specific context for which they are being developed.

In Nigeria, said Ojomo, the government has about 200 dollars to spend per year per citizen. It doesn’t compare well to the 30,000 dollars the U.S. government spends per year for its citizens. That difference helps us to appreciate one of the difficulties of development work, said Ojomo. We recognize that poor countries sometimes suffer under corruption in their governments, but we can also see that they don’t have a lot of time between election cycles and they don’t have much money for sustaining and building their nations. Despite these obstacles, we continue to try to solve issues of poverty by using the same methods that have proven ineffective.

For example, Ojomo said, we try to solve the lack of water, education, infrastructure, health care, government integrity, and money by building wells, schools, roads, airports, bridges, hospitals, institutions, anticorruption measures, and cash transfers, and we don’t understand why these aren’t working. “We begin to appreciate how thorny some of these problems are. It’s not as simple as plopping down the resources – the systems that we think will fix the issue. It’s a little bit more complex than that. And that’s where innovation plays an incredibly important role.”

Financing alone can’t help either, Ojomo suggested. He compared money to fuel. Putting fuel into a run-down, leaking car will not make the car better and isn’t an effective way to use the fuel. Giving money alone to aid development hasn’t worked well; it needs to be part of the solution, but it’s only one component of building a thriving economy.

He described three types of innovation: sustaining innovation, efficiency innovation, and market-creating innovation.

Sustaining innovations make good products better (for example better cameras on smartphones). These focus on markets that already exist – people who have the products and will buy the latest versions.

Efficiency innovations help make good products cheaper, maybe by laying off staff or by outsourcing operations. Efficiency can create more cash flow, but it’s important to look at where the excess cash goes and what is lost. The changes for gaining efficiency can adversely affect the organization, the economy of the region, and the economy of the country.

“That’s where market-creating innovations come into play,” said Ojomo. “Market-creating innovations transform complicated and expensive products, making them simple and affordable so that many more people in society can afford them.”

Many of the things we enjoy today were developed by people who created new markets, Ojomo noted. “They made innovations affordable and available to the average person in the region, and in so doing they began to ignite the engines of prosperity. It’s the primary way we got to where we are today in the United States.”

Organizations focus on different types of innovations, often looking at either product or process, he explained. Market-creating innovation, said Ojomo, focuses on people: “It’s about making sure a product or service gets to people or businesses that currently don’t have access. To do that, we need to build new systems.”

There are implications for businesses, acknowledged Ojomo. Businesses are used to developing new products or changes in process to create efficiency. With market-creating innovation, businesses seek to serve people they have never served before. Ojomo pointed to mobile phones as an example. Not many years ago, it was thought impossible that much of the world would have mobile coverage and access to mobile phones, but today it is a reality, supporting economies, individuals, and other new innovations.

As another example, Ojomo noted a 20-cent package of instant noodles. It’s small and cheap, but the business infrastructure supporting it includes farms, factories, retail shops, warehouse and distribution systems, transport logistics, training, and all of the staff needed to work in those areas.

“All of a sudden a 20-cent pack of noodles starts to look a little bit different to us. It starts to look like development. It starts to look like an engine of prosperity that can propel a nation from poverty.”

Showing a graphic of statistics citing 20 percent access to electricity, an infant mortality rate of 2 out of 5, 10 percent access to secondary school education, and a life expectancy of 45 years, Ojomo asked his audience to guess which country the statistics reflected. Countries such as Afghanistan, Somalia, and Sudan may come to mind, he said, but these are statistics from the United States in about the 1850s to the early 1900s. Some of these demographics are worse than many developing countries have today, but America has moved on from this. “So the question we have to ask in earnest is ‘How did we get from here to where we are today – the richest country in the world today?’”

The U.S. didn’t suddenly become perfect, or fix all of its problems to allow the economy and society to flourish, argued Ojomo. Rather, the change was a slow process driven primarily by new markets that served more and more Americans. As examples, he cited the Singer Corporation, which made sewing machines widely available; the Bank of America, which made loans available to new immigrants and others; and the Ford Motor Company, which made cars available to many.

Displaying a chart of the rise of America’s gross domestic product and innovations along the way, Ojomo asked his audience to consider what would happen if just a few of the major innovations were removed from the chart. Detroit, Mich., shows one result, he suggested. The city was built on innovations in auto manufacturing, but as the industry changed and moved away, the city suffered.

“Some of these cities are starting to show a resurgence, but when you take innovation out of a society, you see that the lifeblood in that society just goes away. [Innovation] is what creates and sustains prosperity for many of us.”

We see roads, schools, and hospitals, and we tend to think they are the things that create prosperity. Ojomo suggests that those things are reflections of prosperity rather than generators of it. In developing countries, even where hospitals have been donated, it can be difficult for regions to sustain them, as the prosperity is not often available yet to maintain the staff, supplies, and maintenance to keep them running.

Ojomo said he is researching to write a sequel to The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty, a book he cowrote with Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen and the Harvard Business Review’s Karen Dillon about the issues outlined in his presentation. While The Prosperity Paradox outlines important problems, he said; in the next book he hopes to outline some solutions. The book’s working title is The Prosperity Process, and Ojomo said he hopes to release it within the next few years.

In researching for this next book, he said, he has discovered some insights about market-creating innovation and the leadership needed to make it work. The most important leadership attribute necessary for market creation, said Ojomo, is love.

Love is not typically thought of as a leadership attribute at all, Ojomo acknowledged, “But when you think about what an innovator has to endure to create a new market, [including] all the people he or she will have to convince that this is a better way, it is consistent across every new market: an innovator’s ability to love people, or a place, or a product, or a process – a way of getting products and services to others that don’t have access – in essence, that innovator’s ability to seek the betterment or the improvement of something outside of themselves, is a necessary condition. I have not yet studied a market that was created without an innovator loving one or more of these things.”

Part of a system, said Ojomo, is hierarchy. Quoting author Donella H. Meadows’s book Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Ojomo noted, “The original purpose of a hierarchy is always to help its originating subsystems do their jobs better.” Reflecting on this, Ojomo outlined how successful leaders serve, rather than expecting to be served. In successful systems, the people who have the most resources serve well: in families, parents care for children; in a building, the strongest materials provide a foundation. Leaders we revere today were not those who demanded service but who served.

“I don’t know of a way to create new markets . . . without building a system that’s designed to serve the average person in society. If we can do it in an economically sustainable way, that creates prosperity for all.”

Before his death in 2020, Clayton Christensen modeled the role of service by asking Ojomo to be a coauthor and cospeaker with him in the publication of The Prosperity Paradox. “He gave me a platform,” said Ojomo, which allowed him to build on this experience, learn, and continue his research and work. This kind of leadership by serving, said Ojomo, “is the thing that’s at the core of helping us create markets that serve as many people as possible. If we’re able to wrap our arms around this, I think we’ll solve many of the world’s issues.”

Ojomo encouraged his audience to wrestle with the complexities we face as we work for better systems. For example, we see that cars create pollution, but we can’t simply all stop using cars immediately to solve the problem.

“If you know about systems, stocks don’t change overnight. I can barely change my behavior overnight, much less an entire system. Once we understand that about systems, then we can say, ‘How can we realistically get from where we are to where we want to go?’ But if we approach the argument always from a moralistic [standpoint] — ‘pollution is bad, this is good’ – how are we going to make the kind of progress we need to make? We can win arguments, we can write amazing papers . . . We’re not going to be here forever. We need to figure out how we’re going to use the time we’re here to build better lives for others. And I think that’s a better way.”